【温馨提示】 购买原稿文件请充值后自助下载。

[全部文件] 那张截图中的文件为本资料所有内容,下载后即可获得。

预览截图请勿抄袭,原稿文件完整清晰,无水印,可编辑。

有疑问可以咨询QQ:414951605或1304139763

摘要:工业机器人是最典型的机电一体化数字化装备,技术附加值很高,应用范围很广,作为先进制造业的支撑技术和信息化社会的新兴产业,将对未来生产和社会发展起着越来越重要的作用。

本文设计了一个工业用SCARA机器人。SCARA机器人(全称Selectively Compliance Articulated Robot Arm)很类似人的手臂的运动,它包含肩关节肘关节和腕关节来实现水平和垂直运动。它是一种工业机器人,具有四个自由度。其中,三个旋转自由度,另外一个是移动自由度。它能实现平面运动,具有柔顺性,全臂在垂直方向的刚度大,在水平方向的柔性大,广泛用于装配作业中。

本文用模块化设计方法设计了SCARA机器人的机械结构。分析了SCARA机器人的运动学正解和逆解,建立了机器人末端位姿误差计算模型并做了运动模拟。

关键字: SCARA 位姿误差

4-DOF SCARA robot design and motion simulation

Student name:RaoXinlong Class:0781052

Supervisor:XuYing

Abstract :Industrial robot is the most typical mechatronic digital equipment, added value and high, wide range of applications, support for advanced manufacturing technology and information society, new industries, and social development of future production will increasingly play a The more important role.

This paper designs an industrial SCARA robot. SCARA robot (full name Selectively Compliance Articulated Robot Arm) is very similar to human arm movement, which includes the shoulder elbow and wrist joints to achieve horizontal and vertical movement. It is an industrial robot has four degrees of freedom. Among them, the three rotational degrees of freedom, the other is the DOF. It can achieve planar motion, with the flexibility, the whole arm in the vertical stiffness, flexibility in the horizontal direction of the large, widely used in assembly operations.

This method was designed with a modular design the mechanical structure of SCARA robot. Analysis of the SCARA robot inverse kinematics, and to establish the position and orientation of robot end of the model error.

Keywords: SCARA analysis

Signature of supervisor:

目录

第一章绪论 1

1.1引言 1

1.2 国内外机器人领域研究现状及发展趋势 1

1.3 SCARA机器人简介 2

1.4平面关节型装配机器人关键技术 4

1.4.1操作机的机构设计与传动技术 4

1.4.2机器人计算机控制技术 4

1.4.3检测传感技术 5

1.5项目的主要研究内容 6

1.5.1项目研究的主要内容、技术方案及其意义 6

1.5.2拟解决的关键问题 7

第二章SCAAR机器人的机械结构设计 7

2.1 SCARA机器人的总体设计 7

2.1.1 SCARA机器人的技术参数 7

2.1.2 SCARA机器人外形尺寸与工作空间 7

2.1.3 SCARA机器人的总体传动方案 8

2.2机器人关键零部件设计计算 10

2.2.1减速机的设计计算 10

2.2.2电机的设计计算 11

2.2.3同步齿型带的设计计算 11

2.2.4滚珠丝杠副的设计计算 13

2.3大臂和小臂机械结构设计 14

2.4腕部机械结构设计 16

2.5小结 17

第三章SCARA机器人的位姿误差建模 17

3.1基于机构精度通用算法的机器人位姿误差建模 17

3.2机构精度通用算法 18

3.2.2通用机器人位姿误差模型 20

机构通用精度模型与机器人位姿误差模型的联系 20

3.2.2机器人位姿误差模型的建立 20

3.3 小结 25

总结 26

参考文献 27

致谢 28

1.1引言

机器人技术是综合了计算机、控制论、机构学、信息和传感技术、人工智能、仿生学等多门学科而形成的高新技术。其本质是感知、决策、行动和交互四大技术的综合,是当代研究十分活跃,应用日益广泛的领域。机器人应用水平是一个国家工业自动化水平的重要标志。

工业机器人既具有操作机(机械本体)、控制器、伺服驱动系统和检测传感装置,是一种仿人操作、自动控制、可重复编程、能在三维空间完成各种作业的自动化生产设备。

目前机器人应用领域主要还是集中在汽车工业,它占现有机器人总数的2.89%。其次是电器制造业,约占16.4%,而化工业则占11.7%。此外,工业机器人在食品、制药、器械、航空航天及金属加工等方面也有较多应用。随着工业机器人的发展,其应用领域开始从制造业扩展到非制造业,同时在原制造业中也在不断的深入渗透,向大、异、薄、软、窄、厚等难加工领域深化、扩展。而新开辟的应用领域有木材家具、农林牧渔、建筑、桥梁、医药卫生、办公家用、教育科研及一些极限领域等非制造业。

一般来说,机器人系统可按功能分为下面四个部分川:

l)机械本体和执行机构:包括机身、传动机构、操作机构、框架、机械连接等内在的支持结构。

2)动力部分:包括电源、电动机等执行元件及其驱动电路。

3)检测传感装置:包括传感器及其相应的信号检测电路。

4)控制及信息处理装置:由硬件、软件构成的机器人控制系统。

1.2 国内外机器人领域研究现状及发展趋势

(1)工业机器人性能不断提高(高速度、高精度、高可靠性、便于操作和维修),而单机价格不断下降,平均单机价格从91年的10.3万美元降至2005年的5万美元。

〔2)机械结构向模块化、可重构化发展。例如关节模块中的伺服电机、减速机、检测系统三位一体化;由关节模块、连杆模块用重组方式构造机器人整机;国外己有模块化装配机器人产品问市。

(3)工业机器人控制系统向基于CP机的开放型控制器方向发展,便于标准化、网络化:器件集成度提高,控制柜日见小巧,且采用模块化结构;大大提高了系统的可靠性、易操作性和可维修性。

(4)机器人中的传感器作用日益重要,除采用传统的位置、速度、加速度等传感器外,装配、焊接机器人还应用了视觉、力觉等传感器,而遥控机器人则采用视觉、声觉、力觉、触觉等多传感器的融合技术来进行环境建模及决策控制;多传感器融合配置技术在产品化系统中己有成熟应用。

(5)虚拟现实技术在机器人中的作用己从仿真、预演发展到用于过程控制,如使遥控机器人操作者产生置身于远端作业环境中的感觉来操纵机器人。

(6)当代遥控机器人系统的发展特点不是追求全自治系统,而是致力于操作者与机器人的人机交互控制,即遥控加局部自主系统构成完整的监控遥控操作系统,使智能机器人走出实验室进入实用化阶段。美国发射到火星上的“索杰纳”机器人就是这种系统成功应用的最著名实例。

(7)机器人化机械开始兴起。从1994年美国开发出“虚拟轴机床”以来,这种新型装置己成为国际研究的热点之一,纷纷探索开拓其实际应用的领域。

1.3 SCARA机器人简介

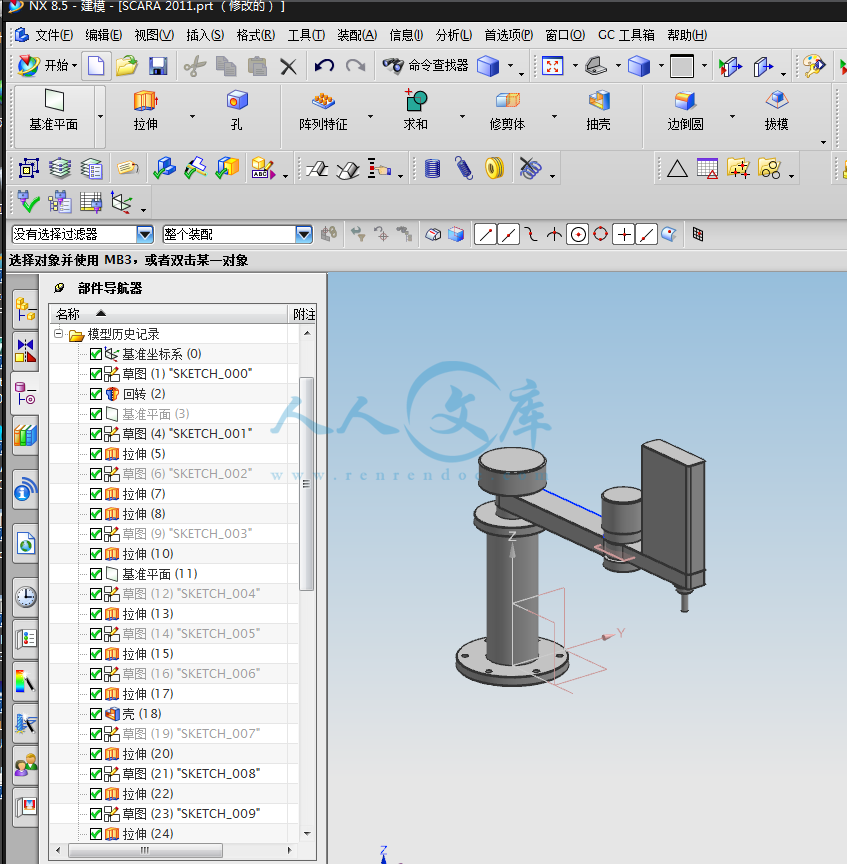

SCARA机器人(如图1一1所示)很类似人的手臂的运动,它包含肩关节、肘关节和腕关节来实现水平和垂直运动,在平面内进行定位和定向,是一种固定式的工业机器人。它具有四个自由度,其中,三个是旋转自由度,一个是移动自由度。3个旋转关节,其轴线相互平行,手腕参考点的位置是由两个旋转关节的角位移p,和pZ,及移动关节的位移Z来决定的。这类机器人结构轻便、响应快,例如Adeptl型SCARA机器人的运动速度可达10m/S,比一般的关节式机器人快数倍。它能实现平面运动,全臂在垂直方向的刚度大,在水平方向的柔性大,具有柔顺性。

图1一1SCARA机器人

图1一2 SCARA机器人装配线

图1一3 SCARA机器人

SCARA机器人最适用于平面定位,广泛应用于垂直方向的装配。广泛应用于需要高效率的装配、焊接、密封和搬运等众多应用领域,具有高刚性、高精度、高速度、安装空间小、工作空间大的优点。由于组成的部件少,因此工作更加可靠,减少维护。有地面安装和顶置安装两种安装方式,方便安装于各种空间。可以用它们直接组成为焊接机器人、点胶机器人、光学检测机器人、搬运机器人、插件机器人等,效率高,占地小,基本免维护。

1.4平面关节型装配机器人关键技术

1.4.1操作机的机构设计与传动技术

由于机器人运行速度快,定位精度高,需要进行运动学与动力学设计计算,解决好操作机结构设计与传动链设计。包括:

(l)重量轻、刚性好、惯性小的机械本体结构设计和制造技术一般采用精巧的结构设计及合理的空间布局,如把驱动电机安装在机座上,就可减少臂部惯量、增强机身刚性;在不影响使用性能的情况下,各种部件尽量采用空心结构。此外,材料的选择对整机性能也是至关重要的。

(2)精确传动轴系的设计、制造及调整技术由伺服电机直接驱动,实现无间隙、无空回、少摩擦、少磨损,提高刚性、精度、可靠性; 各轴承采用预紧措施以保证传动精度和稳定性。

(3)传动平稳、精度高、结构紧凑且效率高的传动机构设计、制造和调整技术由于在解决机械本体结构问题时,往往会对传动机构提出更高要求,有时还存在多级传动,因此要达到上述目的,常采用的方法有:钢带传动,实现无摩擦无间隙、高精度传动;滚珠丝杠传动,可提高传动效率且传动平稳,起动和低速性能好,摩擦磨损小;采用Rv减速器,可缩短传动链。同时合理安排检测系统位置,进一步提高系统精度

1.4.2机器人计算机控制技术

由于自动生产线和装配精度的要求及周边设备的限制,使装配机器人的控制过程非常复杂,并要求终端运动平稳、位姿轨迹精确。现阶段机器人的控制方式主要有两种:一是采用专用的控制系统,如MOTOMAN、FANUC、NACH工等;二是基于PC机的运动控制架构,如KUKA,ABB,工RCS等。在控制领域常涉及的关键技术包括:

(l)点位控制与轨迹控制的双重控制技术一般为装配机器人安装高级编程语言和操作系统。常用的编程方式有示教编程与离线编程。另一方面,合理选择关节驱动器功率和变速比、终端基点密度和基点插补方式,以使运动精确、轨迹光滑。

(2)装配机器人柔顺运动控制技术

由于机器人柔顺运动控制是一种关联的、变参数的非线性控制,能使机器人末端执行器和作业对象或环境之间的运动和状态符合给定要求。这种控制的关键在于选择一种合适的控制算法。

(3)误差建模技术

在机器人运动中,机械制造误差、传动间隙、控制算法误差等会引起机器人末端位姿误差。因此有必要对机器人运动进行误差补偿,建立合理可靠的误差模型,进行公差优化分配,对系统进行误差的标定并采用合适的误差补偿环节。

(4)控制软件技术

将诸如减振算法、前馈控制、预测算法等先进的现代控制理论嵌入到机器人控制器内使机器人具有更精确的定位、定轮廓、更高的移动速度、更短的调整时间,即使在刚性低的机器人结构中也能达到无振动运动等特性,有助于提高机器人性能。

.

1.4.3检测传感技术

检测传感技术的关键是传感器技术,它主要用于检测机器人系统中自身与作业对象、作业环境的状态,向控制器提供信息以决定系统动作。传感器精度、灵敏度和可靠性很大程度决定了系统性能的好坏。检测传感技术包含两个方面的内容:一是传感器本身的研究和应用,二是检测装置的研究与开发。包括:

(1)多维力觉传感器技术

多维力觉传感器目前在国际上也是一个热点,涉及内容多、难度大。它能同时检测三维空间的全力信息,在精密装配、双手协调、零力示教等作业中,有广泛应用。它包括弹性体、传感器头、综合解藕单元、数据处理单元及专用电源等。

(2)视觉技术

视觉技术与检测传感技术的关系类似于人的视觉与触觉的关系,与触觉相比,视觉需要复杂的信息处理技术与高速运算能力,成本较高,而触觉则比较简单,可靠且较易实现。但在有些情况下,视觉可完成对作业对象形状和姿态的识别,可比较全面的获得周围环境数据,在一些特殊装配场合有很大优越性,如在无定位、自主式装配、远程遥控装配、无人介入装配等情况下特别适用。因此如何采用合适的硬件系统对信息进行采集、传输,并对数据进行分析、处理、识别,以得到有用信息用于控制也是一个关键问题。

(3)多路传感器信息融合技术

由于装配机器人中运用多种传感器来采集信息,得到的信息也是多种多样,必须用有效的手段对这些信息进行处理,才能得到有用信息。因此,信息融合技术也成为制约检测技术发展的瓶颈。

(3)检测传感装置的集成化和智能化技术

检测传感装置的集成化能形成复式传感器或矩阵式传感器,而把传感器和测量装置集成则能形成一体化传感器。这些方法都能使传感器功能增加、体积变小、并使检测传感系统性能提高,更加稳定可靠。检测传感装置的智能化则是在检测传感装置中添加微型机或微处理器,使其具有自动判断,自动处理和自动操作等功能。加快系统响应速度、消除或减小环境因素影响、提高系统精度、延长平均无故障时间。

1.5项目的主要研究内容

1.5.1项目研究的主要内容、技术方案及其意义

本课题是要设计一个教学SCARA机器人。作为工业机器人的SCARA己有很多成熟的产品,但大多驱动装置采用伺服电机,传动系统采用RV减速机,由这些部件构成的整机价格昂贵,不适宜于作为教学用途。而教学机器人相对而言对运动精度的要求要比工业场合用的机器人所要求的精度低,对运动速度和稳定性的要求也不高,它只需具备机器人的基本元素,达到一定的精度即可。实际上由步进电机构成的开环系统精度已经很高,能满足教学用途,而且成本比伺服电机构成的闭环、半闭环系统低很多。谐波传动也是精度高、传动平稳并且很成熟的一项传动技术。因此自主开发低成本的教学机器人很有意义。对本机器人的研制,拟采用步进电机作为动力装置,采用谐波减速机作为传动链的主要部件,同时辅以同步齿形带和滚珠丝杠等零部件来构成机器人的机械本体。控制系统采用基于CP的运动控制架构,研究机器人关节空间的轨迹规划算法和笛卡儿空间的直线轨迹规划算法,利用控制卡提供的运动控制库函数在windows环境下用visu1aC++6.0开发控制系统的软件。

项目研究的总体步骤是:

选出最优传动方案一一关键零部件选型一一机械系统三维建模一一零部件工程图和总装图一一控制系统设计一一运动学分析及位姿误差建模一一控制软件的开发以及轨迹规划算法的研究。

1.5.2拟解决的关键问题

(1)抗倾覆力矩问题的解决。SCARA机器人的大臂和小臂重量大,悬伸也大,造成很大的倾覆力矩,影响机器人的性能,通过合理的机械结构设计来加以解决。

(2)机器人的运动学分析以及位姿误差建模方法的研究。根据运动学参数法,建立通用机器人位姿变换方程,在位姿变换方程的基础上建立机器人位姿误差的数学模型,采用矩阵变换直接推导出机器人末端位姿误差与运动学参数误差的函数关系式。

(3)机器人轨迹规划算法的研究。包括给定起点和终点的关节轨迹规划(PTP运动)算法,以及给定起点和终点的直线轨迹规划(CP运动)算法。

第二章SCAAR机器人的机械结构设计

近年来,工业机器人有一个发展趋势:机械结构模块化和可重构化。例如关节模块中的伺服电机、减速机、检测系统三位一体化;由关节模块、连杆模块用重组方式构造机器人整机;国外己有模块化装配机器人产品问市。本章介绍模块化的设计方法在SCARA机器人的结构设计中的应用。

2.1 SCARA机器人的总体设计

2.1.1 SCARA机器人的技术参数

(1) 抓重:≤1kg

(2) 自由度:4

(3) 运动参数:

大臂:±100。(回转角度),角速度≤1.8rad/s

小臂:±50。(回转角度),角速度≤1.8rad /s

手腕回转:±100。(回转角度),角速度≤1.8rad。/s

手腕升降:100mm(升降距离),线速度≤0.01m/s

川公网安备: 51019002004831号

川公网安备: 51019002004831号