接线端子板的冲孔、落料、压弯复合模设计【优秀】【word+10张CAD图纸全套】【冲压复合膜类】【毕业设计】

【外文翻译】【64页@正文28600字】【详情如下】【需要咨询购买全套设计请加QQ1459919609】

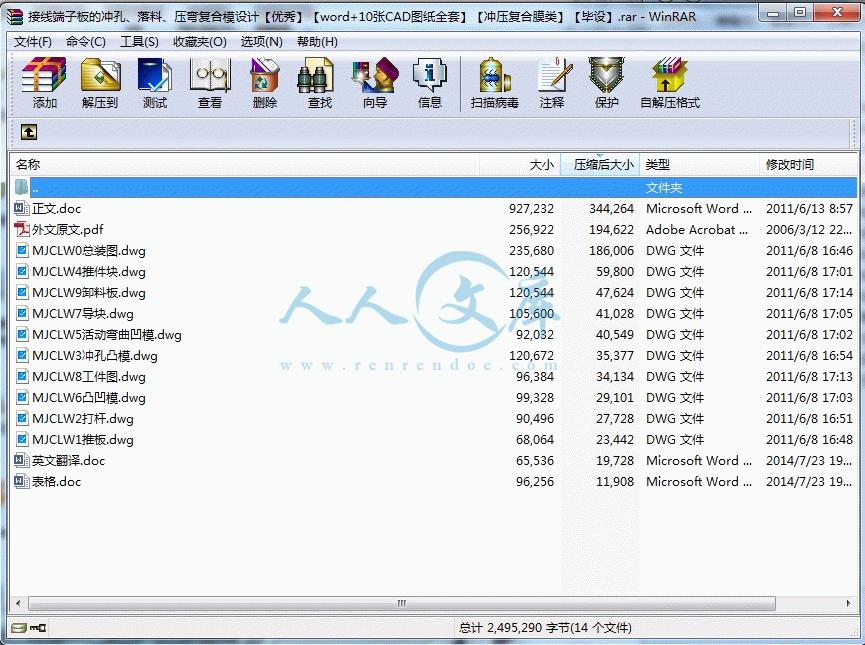

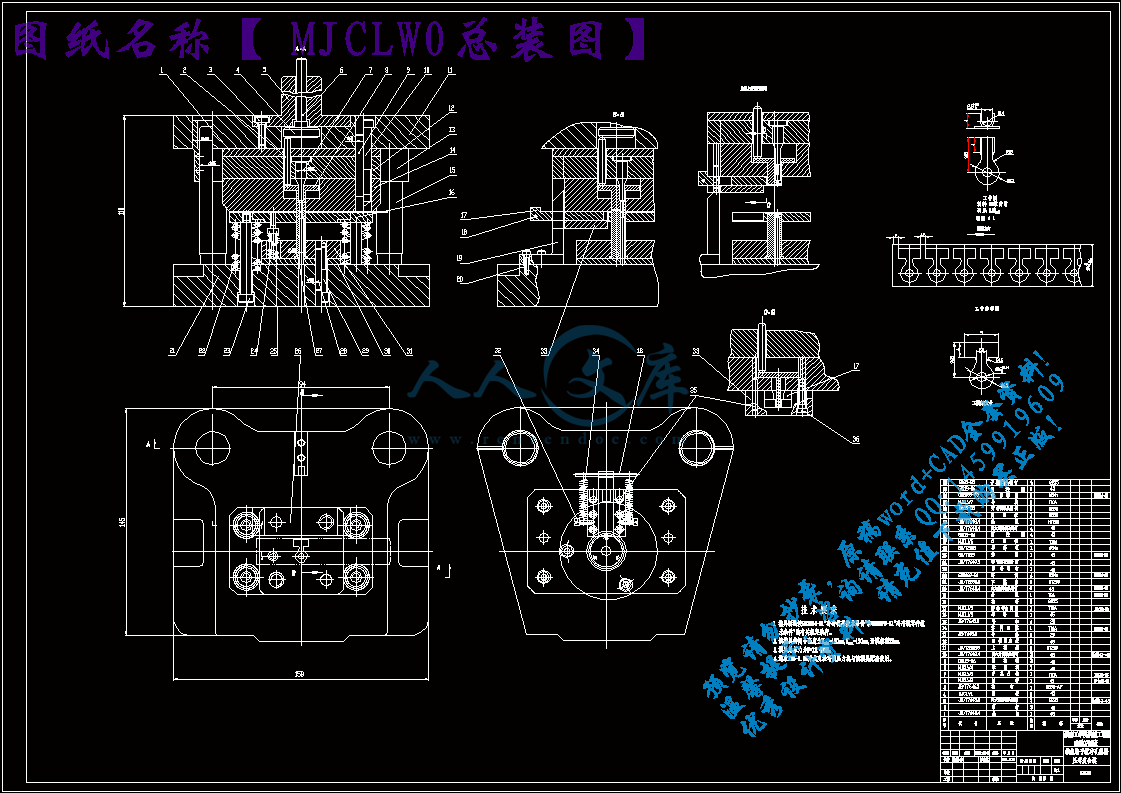

MJCLW0总装图.dwg

MJCLW1推板.dwg

MJCLW2打杆.dwg

MJCLW3冲孔凸模.dwg

MJCLW4推件块.dwg

MJCLW5活动弯曲凹模.dwg

MJCLW6凸凹模.dwg

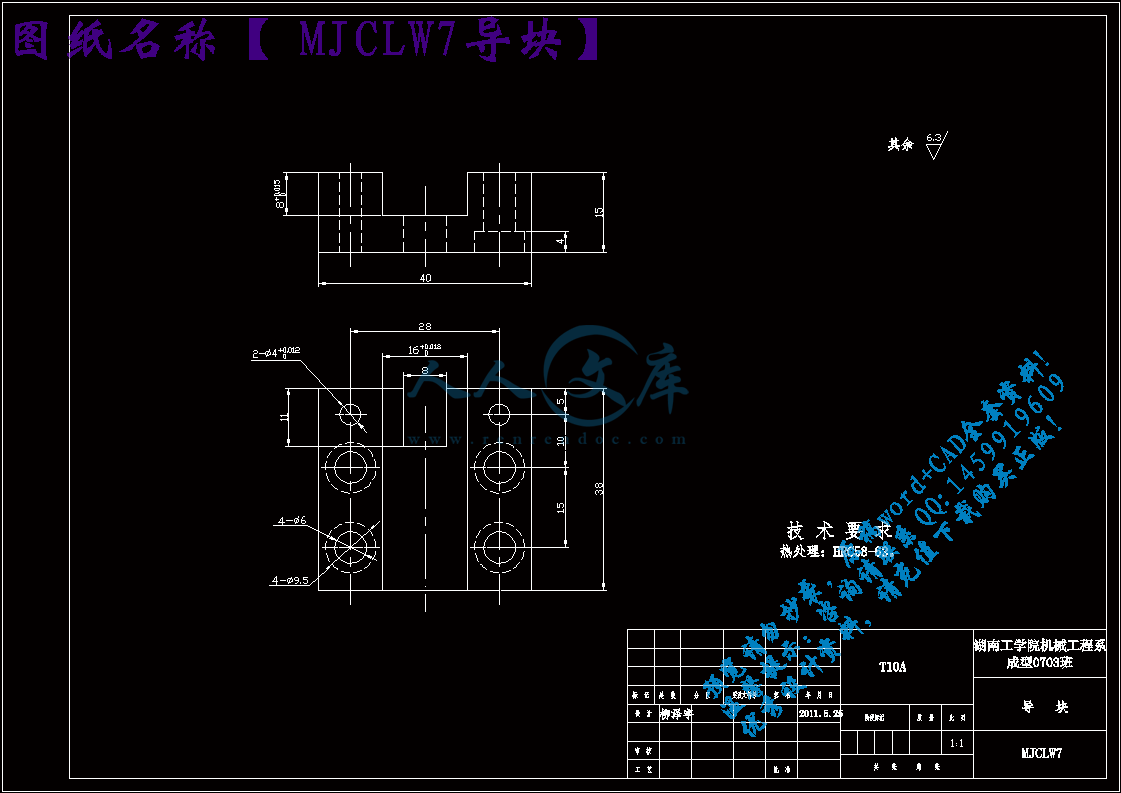

MJCLW7导块.dwg

MJCLW8工件图.dwg

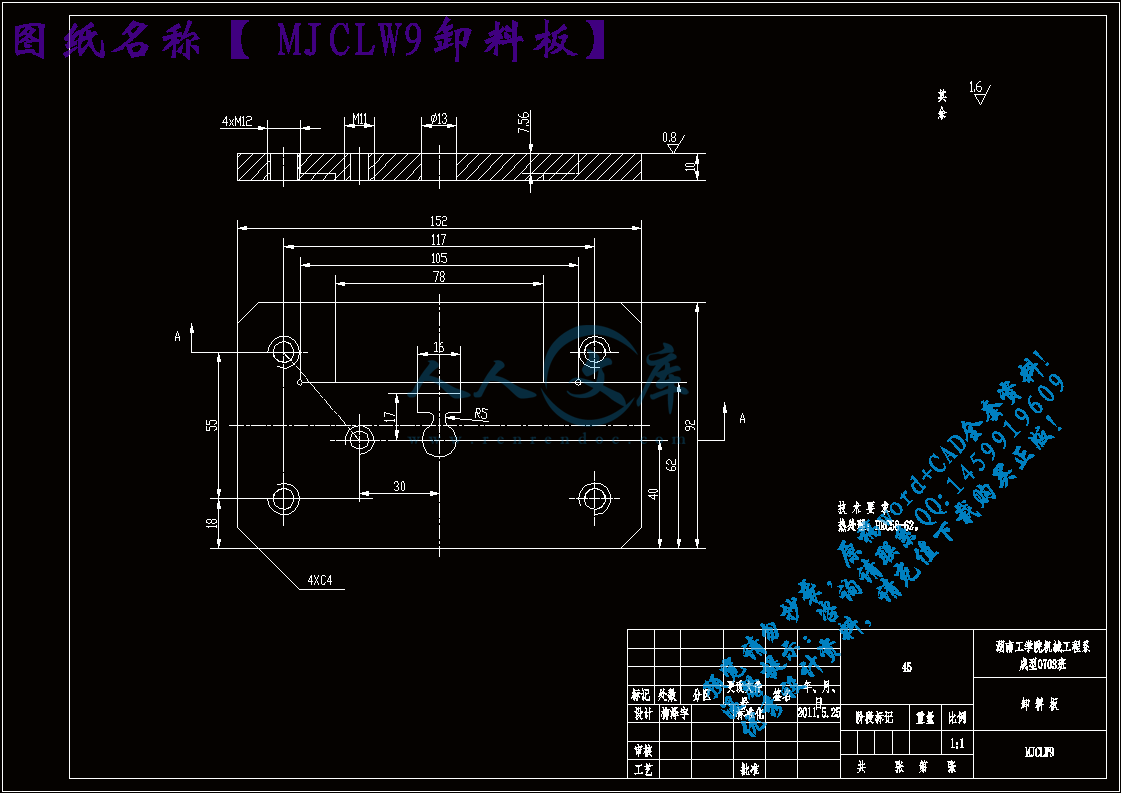

MJCLW9卸料板.dwg

外文原文.pdf

正文.doc

英文翻译.doc

表格.doc

摘 要:阐述了冲孔、落料、压弯复合模的结构设计及工作原理。通过工艺分析,在冲压材料厚度较薄的小型弯曲件时,采用冲孔、落料、弯曲复合模比采用连续或级进模简单。通过冲裁力、顶件力、卸料力等计算,确定模具类型。该模具采用后侧导柱模架结构形式。废料从凸凹模和下底座中所开的槽中排出。本模具性能可靠,运行平稳,能够适应大批量生产要求,提高了产品质量和生产效率,降低劳动强度和生产成本。

关键字:冲压;冲孔、落料、弯曲;复合模

ABSTRACT

Abstract: Expounded punching, blanking, bending modulus of the composite structure design and principle. Process analysis by the stamping of thinner material thickness small curved pieces, will use the punching, blanking, flexural modulus composites than continuous or Progressive Die simple. Punching through, the top pieces, such as the discharge of calculation to determine the type mold. The posterior mold using derivative-scale structures form. Waste from the punch and die and the base under which opened the tank discharges. The mold reliable, stable operation to adapt to the requirements of large-scale production, improve product quality and production efficiency. reduce labor intensity and the cost of production.

Keywords: Ramming; The punch holes, Fall the material curving; Superposable die

目 录

第一章 绪 论1

1.1、冷冲压与模具设计简介1

1.2、我国冲压模具水平状况1

1.3、冲压模具的发展重点与展望4

1.4、本次设计的意义6

第二章 冲压件工艺性分析及冲裁方案的确定7

2.1冲裁件的结构工艺性7

2.2冲裁件尺寸精度和表面粗糙度要求9

2.3冲裁件的尺寸基准9

2.4 冲裁件经济性分析10

2.5冲裁方案的确定10

第三章 排样图的设计及材料利用率的计算12

3.1排样的设计12

3.2搭边的选取14

3.3材料利用率的计算15

第四章 冲裁工艺力的计算17

4.1冲裁力的计算17

4.1.1冲压力的行程曲线17

4.1.2冲裁力的计算公式18

4.1.3降低冲裁力的方法18

4.2卸料力、推件力、和弯曲力等其他力的计算19

4.3冲压压力中心21

第五章 冲压设备的选择24

5.1冲压设备类型的选择24

5.2确定设备的规格24

第六章 冲裁模工作部分设计计算27

6.1冲裁间隙27

6.1.1对冲裁件质量的影响27

6.1.2 对模具寿命的影响28

6.1.3 对冲裁力、卸料力的影响29

6.2合理间隙的选用30

6.3 模具刃口尺寸的计算32

第七章 模具总体设计39

7.1模具类型的选择39

7.2确定送料方式39

7.3定位方式的选择39

7.4卸料、出件方式的选择39

7.5导向方式的选择39

第八章 主要零部件设计41

8.1模具材料的选择41

8.1.1模具材料与热处理41

8.1.2 H62软黄铜的性能41

8.2落料凹模设计42

8.2.1落料凹模刃口形式42

8.2.2落料凹模外形和尺寸的确定42

8.3凸、凹模设计43

8.3.1模具的结构形式和固定方法43

8.3.2凸凹模长度的确定44

8.3.3凸凹模结构设计44

8.4冲孔凸模45

8.4.1冲孔凸模的固定形式45

8.4.2冲孔凸模长度的确定45

8.4.3凸模强度校核45

8.4.4 冲孔凸模的结构47

8.5卸料弹簧的选择47

8.6 打杆的选择48

8.7 活动弯曲凹模的设计49

第九章 标准件的选择50

9.1模架及模柄的选择50

9.2凸模固定板及垫板的选择50

9.3 导尺的选择51

9.4模具闭合高度的校核51

9.6推杆的选择52

9.7螺钉及销钉的选择52

第十章 总装图的设计及绘制54

结 论55

参考文献56

致 谢57

附 录58

第一章 绪 论

1.1、冷冲压与模具设计简介

我国冲压模具无论在数量上,还是在质量、技术和能力等方面都已有了很大发展,但与国民经济需求和世界先进水平相比,差距仍很大,一些大型、精密、复杂、长寿命的高档模具每年仍大量进口,特别是中高档轿车的覆盖件模具,目前仍主要依靠进口。一些低档次的简单冲模,已趋供过于求,市场竞争激烈。

据中国模具工业协会发布的统计材料,2004年我国冲压模具总产出约为220亿元,其中出口0.75亿美元,约合6.2亿元。

根据我国海关统计资料,2004年我国共进口冲压模具5.61亿美元,约合46.6亿元。从上述数字可以得出2004年我国冲压模具市场总规模约为266.6亿元。其中国内市场总需求为260.4亿元,总供应约为213.8亿元,市场满足率为82%。在上述供求总体情况中,有几个具体情况必须说明:一是进口模具大部分是技术含量高的大型精密模具,而出口模具大部分是技术含量较低的中低档模具,因此技术含量高的中高档模具市场满足率低于冲压模具总体满足率,这些模具的发展已滞后于冲压件生产,而技术含量低的中低档模具市场满足率要高于冲压模具市场总体满足率;二是由于我国的模具价格要比国际市场低格低许多,具有一定的竞争力,因此其在国际市场的前景看好,2005年冲压模具出口达到1.46亿美元,比2004年增长94.7%就可说明这一点;三是近年来港资、台资、外资企业在我国发展迅速,这些企业中大量的自产自用的冲压模具无确切的统计资料,因此未能计入上述数字之中。

1.2、我国冲压模具水平状况

近年来,我国冲压模具水平已有很大提高。大型冲压模具已能生产单套重量达50多吨的模具。为中档轿车配套的覆盖件模具国内也能生产了。精度达到1~2μm,寿命2亿次左右的多工位级进模国内已有多家企业能够生产。表面粗糙度达到Ra≦1.5μm的精冲模,大尺寸(Φ≧300mm)精冲模及中厚板精冲模国内也已达到相当高的水平。

1.模具CAD/CAM技术状况

我国模具CAD/CAM技术的发展已有20多年历史。由原华中工学院和武汉733厂于1984年共同完成的精冲模CAD/CAM系统是我国第一个自行开发的模具CAD/CAM系统。由华中工学院和北京模具厂等于1986年共同完成的冷冲模CAD/CAM系统是我国自行开发的第一个冲裁模CAD/CAM系统。上海交通大学开发的冷冲模CAD/CAM系统也于同年完成。20世纪90年代以来,国内汽车行业的模具设计制造中开始采用CAD/CAM技术。国家科委863计划将东风汽车公司作为CIMS应用示范工厂,由华中理工大学作为技术依托单位,开发的汽车车身与覆盖件模具CAD/CAPP/CAM集成系统于1996年初通过鉴定。

在此期间,一汽和成飞汽车模具中心引进了工作站和CAD/CAM软件系统,并在模具设计制造中实际应用,取得了显著效益。1997年一汽引进了板料成型过程计算机模拟CAE软件并开始用于生产。

21世纪开始CAD/CAM技术逐渐普及,现在具有一定生产能力的冲压模具企业基本都有了CAD/CAM技术。其中部分骨干重点企业还具备各CAE能力。

模具CAD/CAM技术能显著缩短模具设计与制造周期,降低生产成本,提高产品质量,已成为人们的共识。在“八五”、“九五”期间,已有一大批模具企业推广普及了计算机绘图技术,数控加工的使用率也越来越高,并陆续引进了相当数量的CAD/CAM系统。如美国EDS的UG,美国ParametricTechnology公司的Pro/Engineer,美国CV公司的CADS5,英国DELCAM公司的DOCT5,日本HZS公司的CRADE及space-E,以色列公司的Cimatron,还引进了AutoCAD、CATIA等软件及法国Marta-Daravision公司用于汽车及覆盖件模具的Euclid-IS等专用软件。国内汽车覆盖件模具生产企业普遍采用了CAD/CAM技术。DL图的设计和模具结构图的设计均已实现二维CAD,多数企业已经向三维过渡,总图生产逐步代替零件图生产。且模具的参数化设计也开始走向少数模具厂家技术开发的领域。

在冲压成型CAE软件方面,除了引进的软件外,华中科技大学、吉林大学、湖南大学等都已研发了较高水平的具有自主知识产权的软件,并已在生产实践中得到成功应用,产生了良好的效益。

快速原型(RP)与传统的快速经济模具相结合,快速制造大型汽车覆盖件模具,解决了原来低熔点合金模具靠样件浇铸模具,模具精度低、制件精度低,样件制作难等问题,实现了以三维CAD模型作为制模依据的快速模具制造,并且保证了制件的精度,为汽车行业新车型的开发、车身快速试制提供了覆盖件制作的保证,它标志着RPM应用于汽车车身大型覆盖件试制模具已取得了成功。

围绕着汽车车身试制、大型覆盖件模具的快速制造,近年来也涌现出一些新的快速成型方法,例如目前已开始在生产中应用的无模多点成型及激光冲击和电磁成型等技术。它们都表现出了降低成本、提高效率等优点。

2.模具设计与制造能力状况

在国家产业政策的正确引导下,经过几十年努力,现在我国冲压模具的设计与制造能力已达到较高水平,包括信息工程和虚拟技术等许多现代设计制造技术已在很多模具企业得到应用。

虽然如此,我国的冲压模具设计制造能力与市场需要和国际先进水平相比仍有较大差距。这些主要表现在高档轿车和大中型汽车覆盖件模具及高精度冲模方面,无论在设计还是加工工艺和能力方面,都有较大差距。轿车覆盖件模具,具有设计和制造难度大,质量和精度要求高的特点,可代表覆盖件模具的水平。虽然在设计制造方法和手段方面已基本达到了国际水平,模具结构功能方面也接近国际水平,在轿车模具国产化进程中前进了一大步,但在制造质量、精度、制造周期等方面,与国外相比还存在一定的差距。

标志冲模技术先进水平的多工位级进模和多功能模具,是我国重点发展的精密模具品种。有代表性的是集机电一体化的铁芯精密自动阀片多功能模具,已基本达到国际水平。

但总体上和国外多工位级进模相比,在制造精度、使用寿命、模具结构和功能上,仍存在一定差距。

汽车覆盖件模具制造技术正在不断地提高和完善,高精度、高效益加工设备的使用越来越广泛。高性能的五轴高速铣床和三轴的高速铣床的应用已越来越多。NC、DNC技术的应用越来越成熟,可以进行倾角加工和超精加工。这些都提高了模具型面加工精度,提高了模具的质量,缩短了模具的制造周期。

模具表面强化技术也得到广泛应用。工艺成熟、无污染、成本适中的离子渗氮技术越来越被认可,碳化物被覆处理(TD处理)及许多镀(涂)层技术在冲压模具上的应用日益增多。真空处理技术、实型铸造技术、刃口堆焊技术等日趋成熟。激光切割和激光焊接技术也得到了应用。

3.专业化程度及分布状况

我国模具行业专业化程度还比较低,模具自产自配比例过高。国外模具自产自配比例一般为30%,我国冲压模具自产自配比例为60%。这就对专业化产生了很多不利影响。现在,技术要求高、投入大的模具,其专业化程度较高,例如覆盖件模具、多工位级进模和精冲模等。而一般冲模专业化程度就较低。由于自配比例高,所以冲压模具生产能力的分布基本上跟随冲压件生产能力的分布。但是专业化程度较高的汽车覆盖件模具和多工位、多功能精密冲模的专业生产企业的分布有不少并不跟随冲压件能力分布而分布,而往往取决于主要投资者的决策。例如四川有较大的汽车覆盖件模具的能力,江苏有较强的精密冲模的能力,而模具的用户大都不在本地。

1.3、冲压模具的发展重点与展望

发展重点的选取应根据市场需求、发展趋势和目前状况来确定。可按产品重点、技术重点和其他重点分别叙述。

1、冲压模具产品发展重点。

冲压模具共有7小类,并有一些按其服务对象来称呼的一些种类。目前急需发展的是汽车覆盖件模具,多功能、多工位级进模和精冲模。这些模具现在产需矛盾大,发展前景好。

汽车覆盖件模具中发展重点是技术要求高的中高档轿车大中型覆盖件模具,尤其是外覆盖件模具。高强度板和不等厚板的冲压模具及大型多工位级进模、连续模今后将会有较快的发展。多功能、多工位级进模中发展重点是高精度、高效率和大型、高寿命的级进模。精冲模中发展重点是厚板精冲模大型精冲模,并不断提高其精度。

2、冲压模具技术发展重点。

模具技术未来发展趋势主要是朝信息化、高速化生产与高精度化发展。因此从设计技术来说,发展重点在于大力推广CAD/CAE/CAM技术的应用,并持续提高效率,特别是板材成型过程的计算机模拟分析技术。模具CAD、CAM技术应向宜人化、集成化、智能化和网络化方向发展,并提高模具CAD、CAM系统专用化程度。

为了提高CAD、CAE、CAM技术的应用水平,建立完整的模具资料库及开发专家系统和提高软件的实用性十分重要。从加工技术来说,发展重点在于高速加工和高精度加工。高速加工目前主要是发展高速铣削、高速研抛和高速电加工及快速制模技术。高精度加工目前主要是发展模具零件精度1μm以下和表面粗糙度Ra≦0.1μm的各种精密加工。提高模具标准化程度,搞好模具标准件生产供应也是冲压模具技术发展重点之一。

为了提高冲压模具的寿命,模具表面的各种强化超硬处理等技术也是发展重点。

对于模具数字化制造、系统集成、逆向工程、快速原型/模具制造及计算机辅助应用技术等方面形成全方位解决方案,提供模具开发与工程服务,全面提高企业水平和模具质量,这更是冲压模具技术发展的重点。

3、其他发展重点及展望。

其他发展重点及展望的内涵十分丰富,这里只就管理、专业化与标准化及行业调整三个方面作一些分析。

企业管理是一个系统工程,是一门学问,是科学技术。与工业发达国家模具企业相比,在某种意义上说,我们的管理落后更甚于技术落后。因此改进管理十分重要,且任务繁重,目前模具企业的管理有许多形式,各有其适应对象,但搞好信息化建设,逐步实现信息化管理已成为发展方向,行业也对此有共识。

由于历史和体制上的原因,我国模具专业化和标准化水平一直很低,其中冲压模具的专业化比塑料模和压铸模更低。这在一定程度上妨碍了冲压模具的发展,根据国内外模具专业化情况来看,专业化可以有多层意思:1)模具生产独立于其他产品生产,专业生产模具外供;2)按模具种类划分,专门从事某一类模具(如冲压模具)生产;3)在某一类模具中,按其服务对象或模具工艺及尺寸大小,选取该类模具中的某种模具(例如汽车覆盖件模具、多工位级进模具、精冲模具等等)进行专业化生产;4)专业生产模具中的某一些零件(如模架、冲头、弹性元件等)供给模具生产企业;5)按工序开展专业化协作。例如目前社会上专门从事模具设计的公司、专门进行型腔加工或电加工协作的企业、专门接受测量或热处理委托业务的企业及专业从事抛光业务的企业等等,这种多层次的专业化促进了模具行业的发展。但专业化的路途仍旧遥远,必须加快进程才能适应形势。因此,这也是发展重点。

行业调整是一个十分繁重的任务,模具行业更是如此。模具行业面临的调整任务主要有:

(1)模具企业组织结构的调整。使模具分厂(车间)独立出来,成为面向社会、自负盈亏的独立法人是调整的方向。模具企业按小而精、小而专、小而特的方向发展,并且在条件成熟情况下企业之间进行联合,以及发展产、学、研和科、工、贸相结合的联合体,也是调整的方向。规模效应也引起大家的重视。

(2)模具产品结构的调整。随着汽车工业、电子信息工业和家电工业的发展,冲压模具市场结构正在发生很大变化。与此相适应,冲压模具产品结构必须进行相应的调整。例如汽车覆盖件模具、汽车零件精冲模具、高精度高难度的引线框架冲模、接插件多工位级进模、各种电机定转子级进冲模等,其产品种类和产量必将有很大发展,有关企业必须根据市场需求来调整其产品结构。总体来看,应不断提高技术含量的大型、精密、复杂、长寿命模具的比例。

(3)模具技术结构的调整。21世纪已进入信息时代,信息时代的发展日新月异,模具行业和企业要发展必须把握时代脉搏,自觉主动地调整自已的技术结构。传统的模具设计制造技术必须用先进适用的高新技术进行改造,模具的技术含量必将逐步而快速地提高,现代化工业企业管理技术也必将逐步替代作坊式的管理模式。模具行业和模具企业,只有不断进行技术结构的调整,才能在瞬息万变的市场经济中立于不败之地。

(4)模具进出口结构的调整。2005年,我国冲压模具进口7.26亿美元,出口1.97亿美元,进出口相抵后净进口5.29亿美元,进出口之比3.7:1。我国的冲压模具出口量只占生产量的5%。这样的结构明显不合理。模具工业发达国家,模具产出中一般都有30%左右的出口,出口模具大大多于进口模具。我们虽然不可能在短时间内达到模具工业发达国家一样的进出口结构,但努力扩大出口,逐步改善结构,经过若干年努力,尽量做到进出口基本平衡,则应该是我们调整的目标。

在信息化带动工业化发展的今天,在经济全球化趋向日渐加速的情况下,我国冲压模具必须尽快提高水平。通过改革与发展,采取各种有效措施,在冲压模具行业全体职工的共同努力奋斗之下,我国冲压模具也一定会不断提高水平,逐渐缩小与世界先进水平的差距。“十一五”期间,在科学发展观指导下,不断提高自主开发能力、重视创新、坚持改革开放、走新型工业化道路,将速度效益型的增长模式逐步转变到质量和水平效益型轨道上来,我国的冲压模具的水平也必然会更上一层楼。

1.4、本次设计的意义

这次毕业设计,是对我四年大学学习效果的有效检验方式。通过这次设计,能把课本上的知识和现实生产工作有机结合在一起,对即将走上社会工作的我们是一个很好的锻炼。在设计过程中,要查阅大量的资料,和老师、同学做良好的沟通,这也能培养我细心的习惯和团队合作精神,这对我以后的工作、生活是有很大帮助的。

第二章 冲压件工艺性分析及冲裁方案的确定

冲裁件的工艺性,是指冲裁件对冲裁工艺的适应性,即冲裁件的形状结构、尺寸大小、尺寸偏差、形位公差与尺寸基准等是否符合冲裁工艺的要求。冲裁件的工艺性对冲裁工件的质量、材料利用率、生产率、模具制造难易、模具寿命、操作方式及冲压设备的选用等都有很大的影响。一般情况下,对冲裁件工艺性影响最大是几何形状、尺寸、精度要求。良好的冲裁件工艺性能满足材料省、工序少、产品质量稳定、模具较易加工、操作方便且寿命较高等要求,从而显著降低冲裁件的制造成本。

参考文献

[1] 吴宗泽,罗圣国.机械设计课程设计手册.北京:高等教育出版社,1999 (2004重印)

[2] 姜奎华.冲压工艺与模具设计.北京:机械工业出版社,1998.5

[3] 王卫卫.材料成型设备.北京:机械工业出版社,2004.8

[4] 郝彬海.冲压模具简明设计手册.北京:化学工业出版社,2004.11

[5] 储凯,许斌,李先民,李维民.机械工程材料.重庆:重庆大学出版社2004.2

[6] 中国模具工业协会标准委员会编.中国模具标准件手册.上海:上海科学普及出版社,1989.

[7] 中国机械工程学会,中国模具设计大典委员会.中国模具设计大典.江西:江西科学技术出版社,2003.1

[8] 国家标准总局. 《冷冲压国家标准》.北京:《冷冲压国家标准》,1989

[9] 李天佑.《冲模图册》.北京:机械工业出版社,1998.

[10] 丁聚松.《冷冲模设计》.北京:机械工业出版社,1999.

[11] 赵孟栋主编.冷冲模设计(第2版).北京:机械工业出版社,1997.

[12] 王孝培主编.冲压手册.北京:机械工业出版社,1990.

[13] 肖景容,姜奎华主编.冲压工艺学.北京:机械工业出版社,1990.

川公网安备: 51019002004831号

川公网安备: 51019002004831号