【温馨提示】 购买原稿文件请充值后自助下载。

以下预览截图到的都有源文件,图纸是CAD,文档是WORD,下载后即可获得。

预览截图请勿抄袭,原稿文件完整清晰,无水印,可编辑。

有疑问可以咨询QQ:414951605或1304139763

摘 要

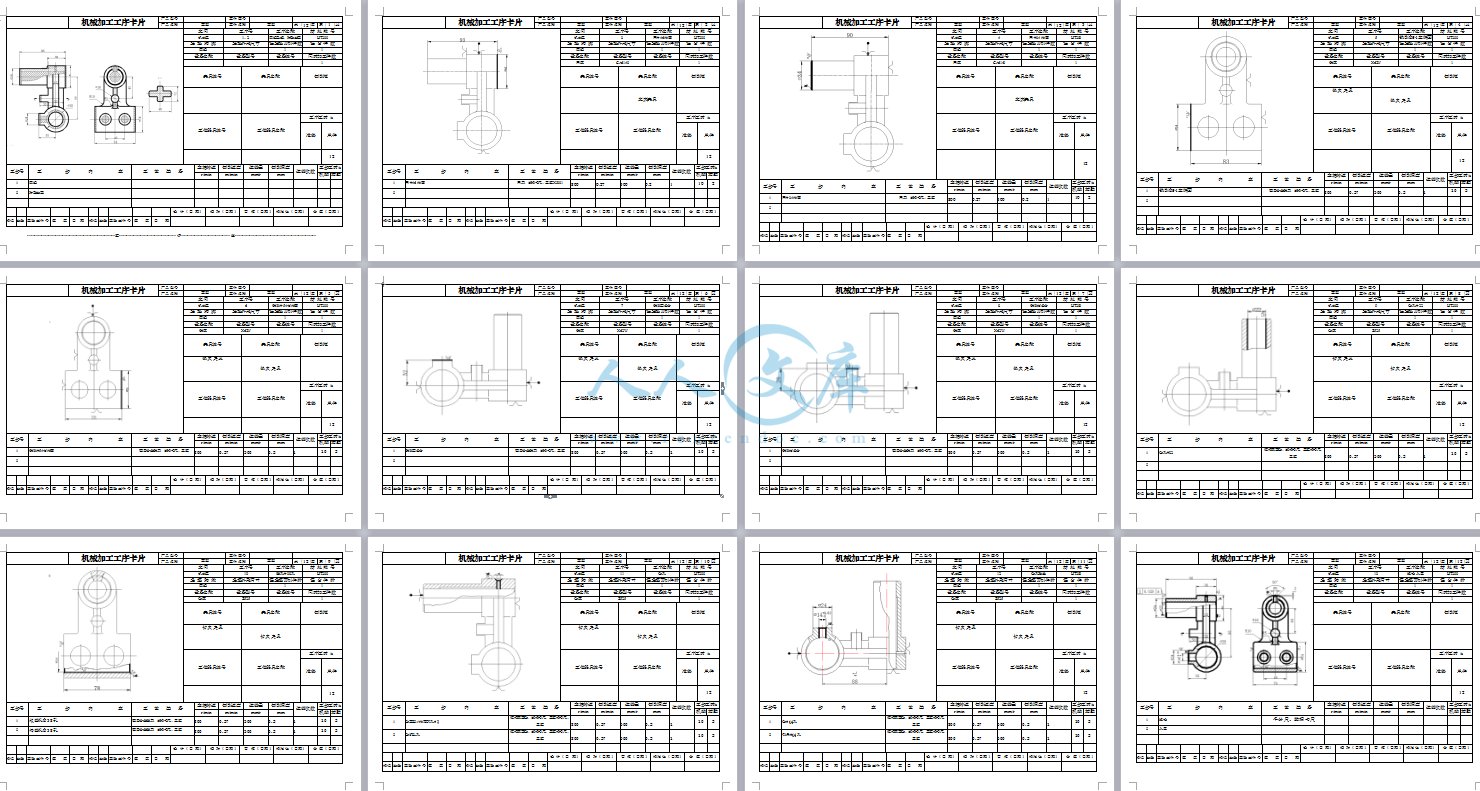

本文是对支架零件的加工工艺规程进行设计,并针对其中某一道工序进行基于液压的专用夹具设计,并进行了另一工序的普通夹具设计。支架零件作为叉架类零件,其主要加工表面是平面及孔。按照机械加工工艺要求,遵循先面后孔的原则,并将孔与平面的加工明确划分成粗加工和精加工阶段以保证加工精度。基准选择以支架大外圆端面作为粗基准,以支架大外圆端面与两个工艺孔作为精基准,确定了其加工的工艺路线和加工中所需要的各种工艺参数。并按要求对其中一道工序进行了基于液压夹紧的专用夹具设计,在设计中计算了此道工序所受的切削力及切削力矩,进而确定了液压缸的负载,选定整个液压系统的压力,从而确定了液压缸的各参数,绘制了液压夹紧的专用夹具总图。整个加工过程均选用万能机床。

关键词 支架;加工工艺;液压;专用夹具

目 录

摘 要III

AbstractIV

目 录V

1 绪论1

1.1 本课题的研究内容和意义1

1.2 国内外的发展概况1

1.3 本课题应达到的要求2

2 支架零件的三维造型3

3 零件的分析10

3.1 零件的作用10

3.2 零件的工艺分析10

4 工艺规程设计11

4.1 确定毛坯的制造形式11

4.2 工艺过程设计所应采取的相应措施11

4.3 定位基准面的选择11

4.3.1 粗基准的选择11

4.3.2 精基准的选择12

4.4 制定工艺路线12

4.4.1 工艺路线方案一:12

4.4.2 工艺路线方案二:12

4.4.3 工艺方案的比较与分析13

4.5 机械加工余量、工序尺寸及毛坯尺寸的确定13

4.6 确定切削用量及基本工时15

4.6.1 工序三:铣的端面,铣的端面,铣×2的端面。16

4.6.2 工序四:钻-扩-铰-精铰的孔。18

4.6.3 工序五:钻-扩-铰-精铰的孔。20

4.6.4 工序六:钻孔,锪孔,倒角。22

4.6.5 工序七:铣端面。23

4.6.6 工序八:粗镗-半精镗-精镗的孔。23

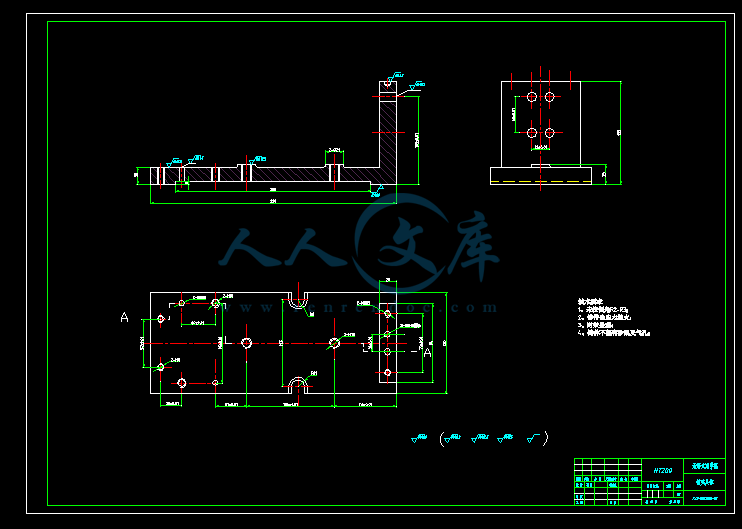

5 基于液压夹紧的专用夹具设计26

5.1 设计主旨26

5.2 夹具设计26

5.2.1 定位基准的选择26

5.2.2 定位误差分析26

5.2.3 铣夹具设计的基本要求27

5.3 液压缸的设计计算27

5.3.1 切削力及切削力矩的计算与分析27

5.3.2 确定系统的工作压力29

5.3.3 确定液压缸的几何参数30

5.4 确定液压泵规格和电动机功率及型号32

5.4.1 确定液压泵规格32

5.5 确定各类控制阀33

5.6 管道通径与材料及管接头的选用33

6 专用普通夹具设计35

6.1 设计主旨35

6.2 夹具设计35

6.2.1 定位基准的选择35

6.2.2 切削力及夹紧力计算35

6.2.3 钻套、衬套、钻模板设计36

6.2.4 活动V形块的设计36

6.2.5 夹具体的设计36

6.2.6 夹具精度分析36

6.2.7 夹具设计及操作的简要说明37

7 结论与展望38

7.1 结论38

7.2 不足之处及未来展望38

毕业设计小结39

致谢41

参考文献42

1 绪论

1.1 本课题的研究内容和意义

机械的加工工艺及夹具设计是在完成大学的全部课程之后,进行的一次理论联系实际的综合运用,使我对专业知识、技能有了进一步的提高,为以后从事专业技术的工作打下基础。机械加工工艺是实现产品设计,保证产品质量、节约能源、降低成本的重要手段,合理的机械加工工艺过程是企业进行生产准备、计划调度、加工操作、生产安全、技术检测和健全劳动组织的重要依据,也是企业上品种、上质量、上水平,加速产品更新,提高经济效益的技术保证。

合理的机械加工工艺文件不仅能提高一个企业的技术革新能力,而且可以较大程度地提高企业的利润,因而合理地编制零件的加工工艺文件就显得时常重要。机械加工工艺文件的合理性也会受到企业各方面因素的制约,比如企业的生产设备、工人的技术水平及夹具的设计水平等,其中比较重要的是夹具的设计和生产。夹具是机械加工系统的重要组成部分,无论是传统的制造,或是现代制造系统,夹具设计都非常重要。优化夹具设计可以使产品劳动生产率得到提高,降低生产成本,使加工精度得到提高和保证,同时可以拓宽机床的使用范围,而且在保证精度的前提下可使产品效率提高、成本降低。在企业信息化和激烈的市场竞争的要求下,企业对夹具的设计及制造要求更高。所以对机械的加工工艺及夹具设计具有十分重要的意义。

因而不仅要合理结合企业的生产实际来进行零件加工工艺文件的编制,而且还要根据零件的加工要求和先进的加工机床来设计先进高效的夹具。

该课题主要是为了培养学生开发、设计和创新机械产品的能力,要求学生能够结合常规机床与零件加工工艺,针对实际使用过程中存在的金属加工中所需要的三维造型、机床的驱动及工件夹紧问题,综合所学的机械三维造型、机械理论设计与方法、机械加工工艺及装备、液压与气动传动等知识,对高效、快速夹紧装置进行改进设计,从而实现金属加工机床驱动与夹紧的半自动控制。

在设计液压系统装置时,在满足产品工作要求的情况下,应尽可能多的采用标准件,提高其互换性要求,以减少产品的设计生产成本。

川公网安备: 51019002004831号

川公网安备: 51019002004831号