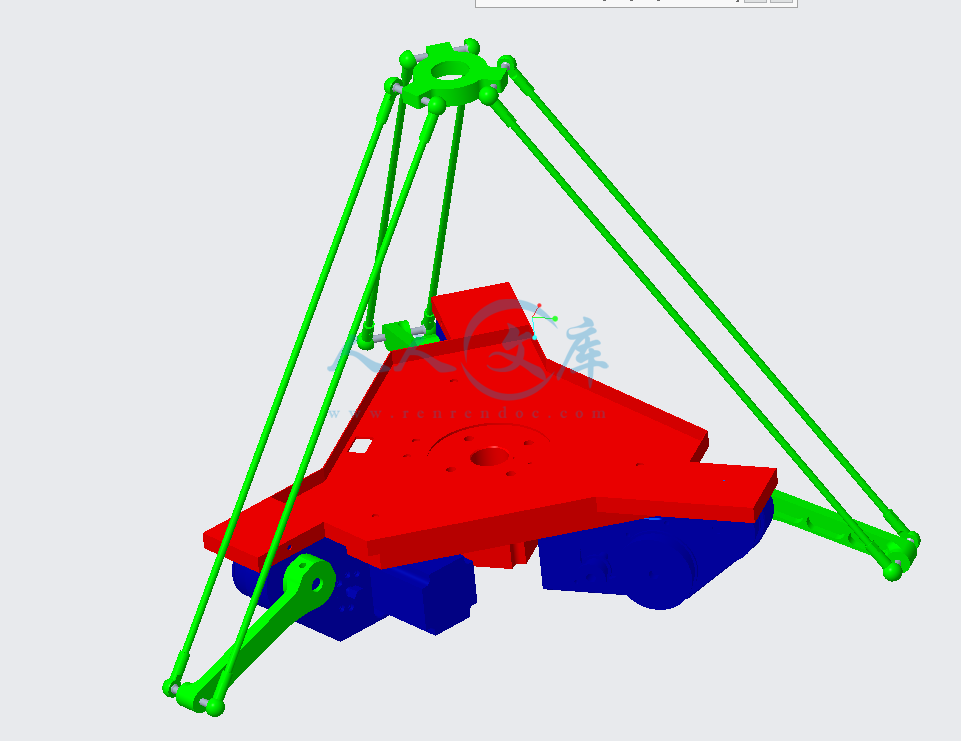

三自由度Delta并联机器人的设计与仿真(含CADCREO三维图)

收藏

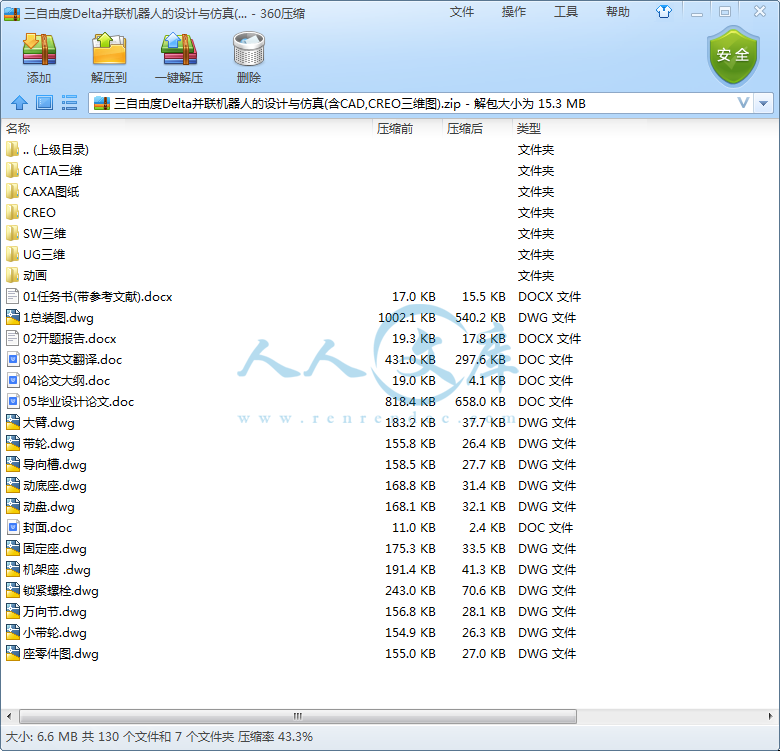

资源目录

压缩包内文档预览:

编号:60193809

类型:共享资源

大小:6.74MB

格式:ZIP

上传时间:2020-03-21

上传人:机****料

认证信息

个人认证

高**(实名认证)

河南

IP属地:河南

80

积分

- 关 键 词:

-

自由度

Delta

并联

机器人

设计

仿真

CADCREO

三维

- 资源描述:

-

- 内容简介:

-

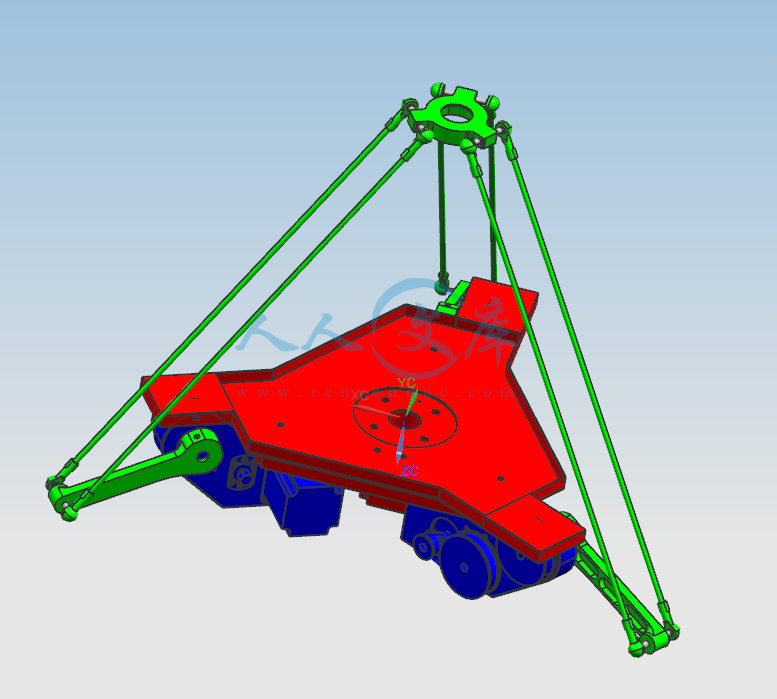

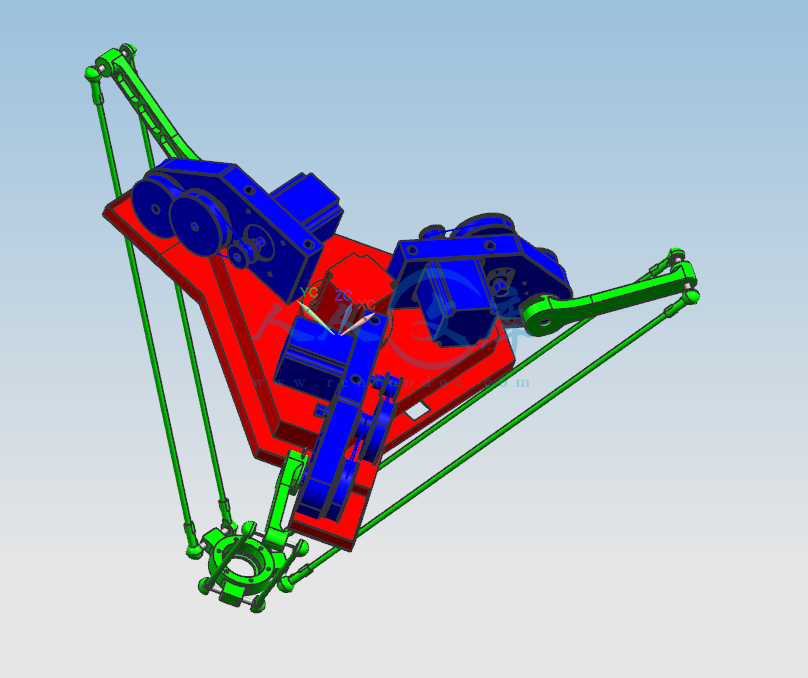

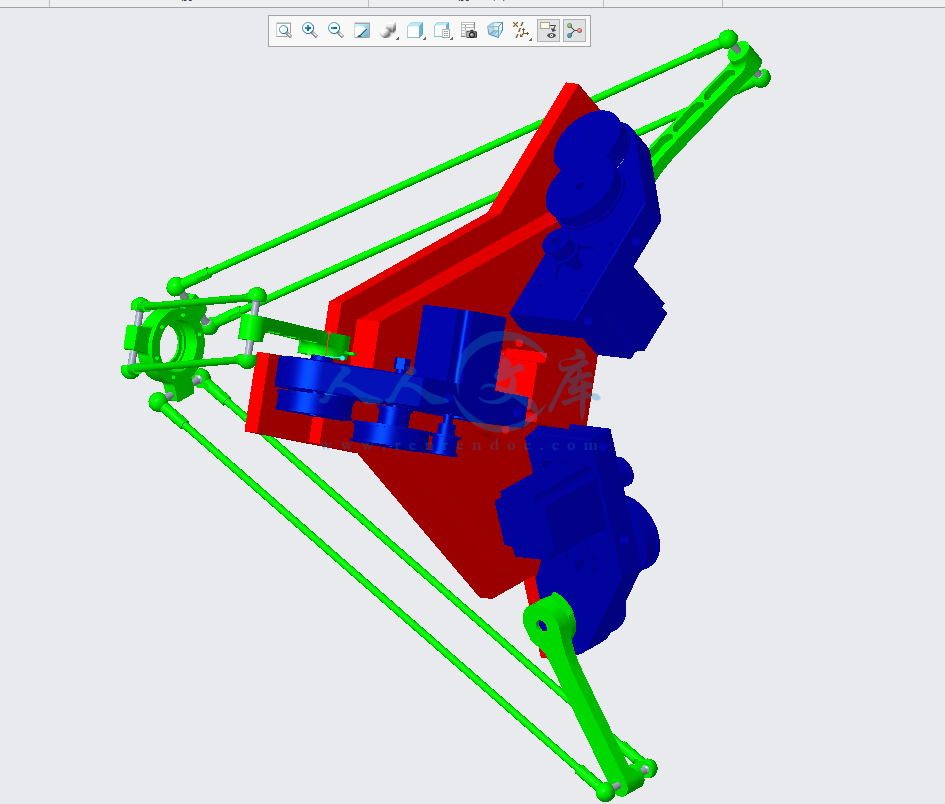

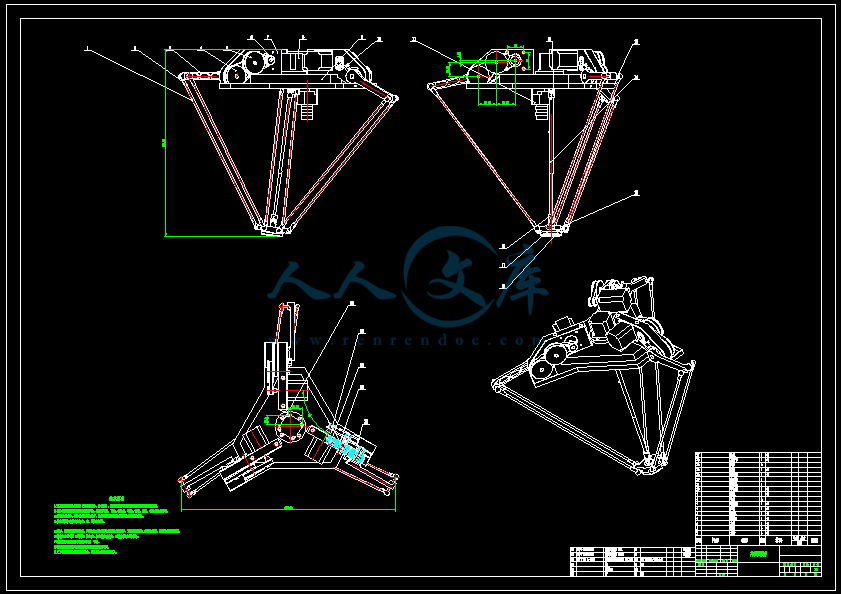

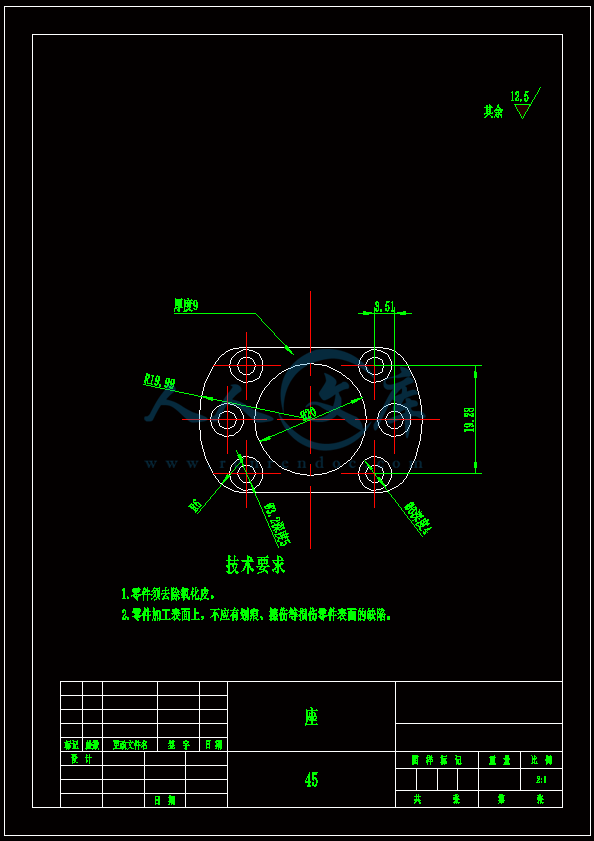

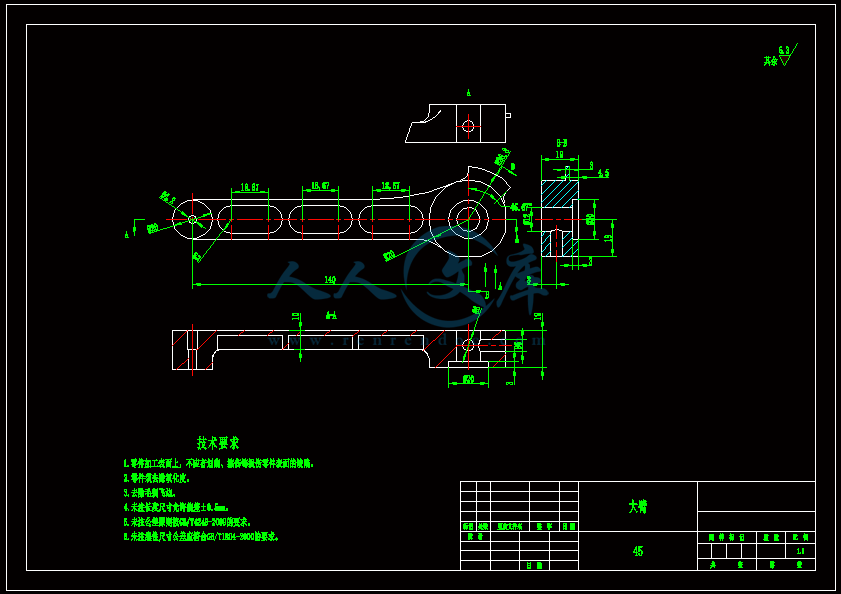

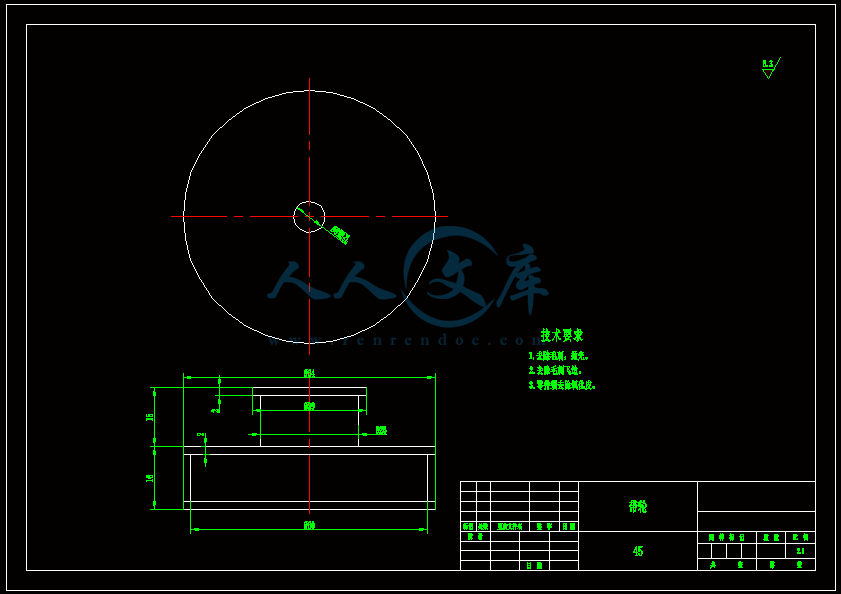

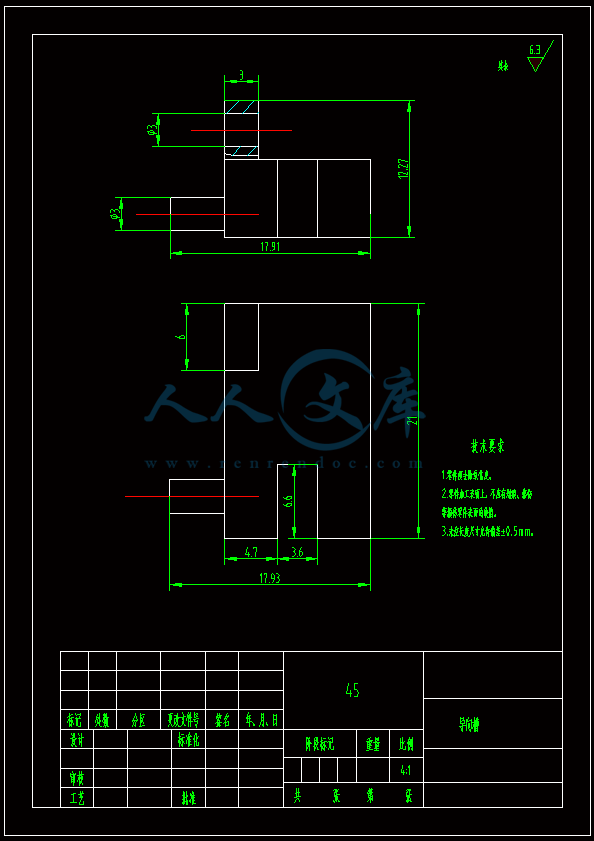

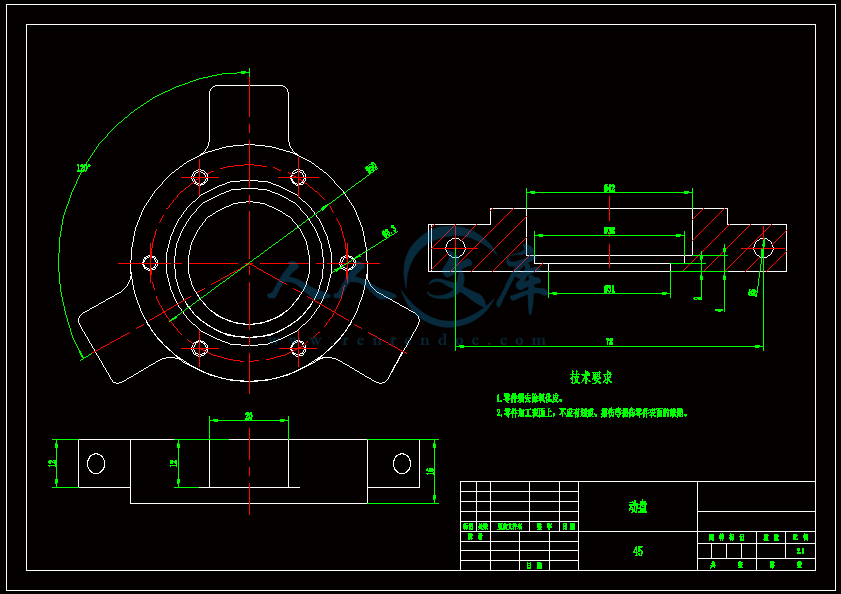

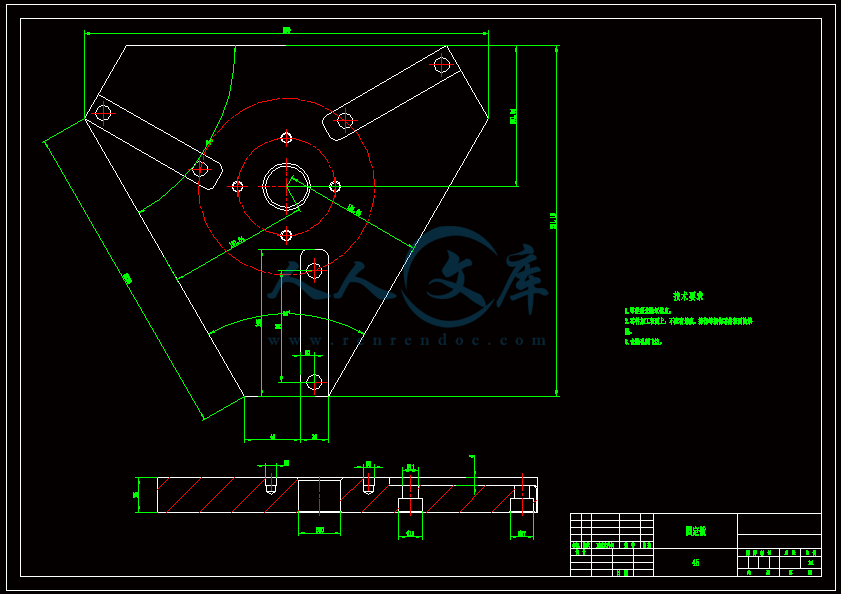

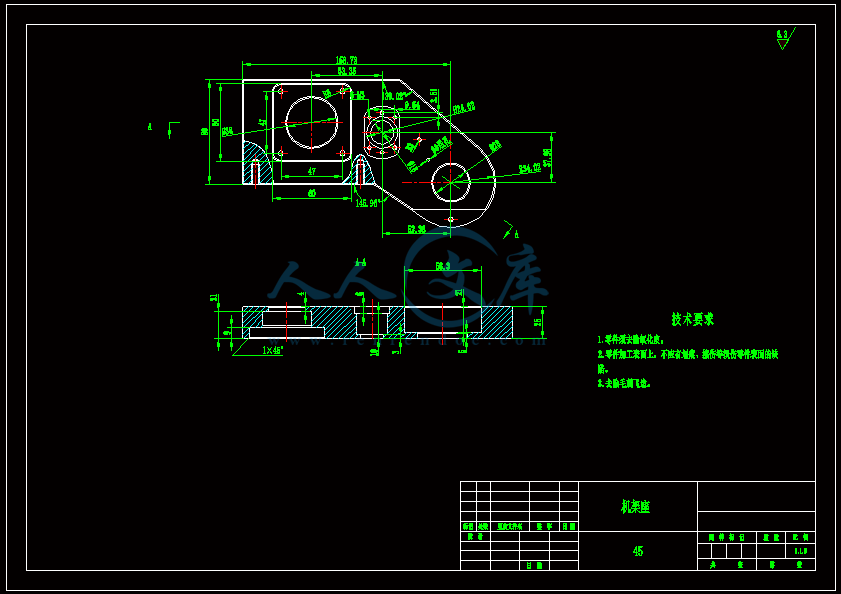

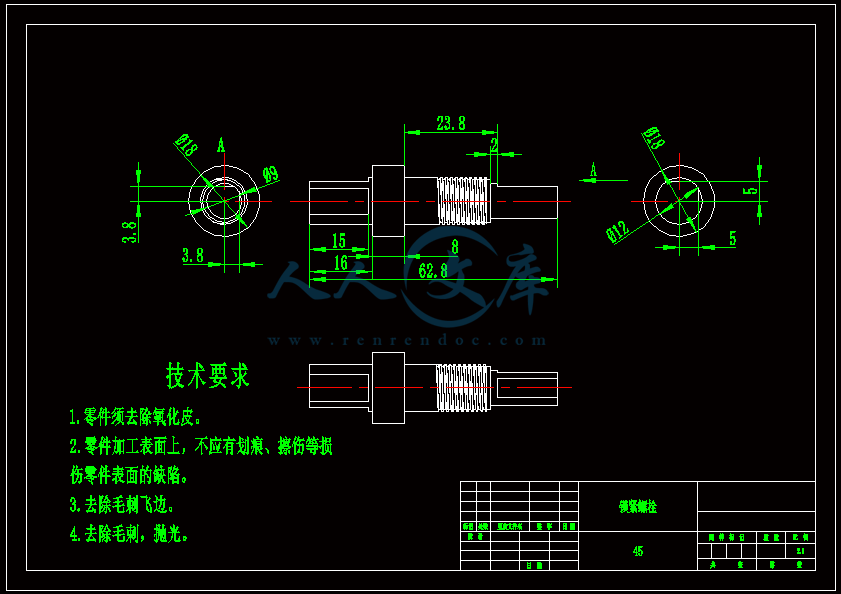

毕 业 设 计(论 文)任 务 书设计(论文)题目:三自由度Delta并联机器人的设计与仿真 学生姓名:专业:所在学院:指导教师:职称:发任务书日期:年月日 任务书填写要求1毕业设计(论文)任务书由指导教师根据各课题的具体情况填写,经学生所在专业的负责人审查、系(院)领导签字后生效。此任务书应在毕业设计(论文)开始前一周内填好并发给学生。2任务书内容必须用黑墨水笔工整书写,不得涂改或潦草书写;或者按教务处统一设计的电子文档标准格式(可从教务处网页上下载)打印,要求正文小4号宋体,1.5倍行距,禁止打印在其它纸上剪贴。3任务书内填写的内容,必须和学生毕业设计(论文)完成的情况相一致,若有变更,应当经过所在专业及系(院)主管领导审批后方可重新填写。4任务书内有关“学院”、“专业”等名称的填写,应写中文全称,不能写数字代码。学生的“学号”要写全号,不能只写最后2位或1位数字。 5任务书内“主要参考文献”的填写,应按照金陵科技学院本科毕业设计(论文)撰写规范的要求书写。6有关年月日等日期的填写,应当按照国标GB/T 740894数据元和交换格式、信息交换、日期和时间表示法规定的要求,一律用阿拉伯数字书写。如“2002年4月2日”或“2002-04-02”。毕 业 设 计(论 文)任 务 书1本毕业设计(论文)课题应达到的目的: 本毕业设计课题的主要目的是培养学生综合运用所学的基础理论、专业知识和专业基本技能分析和解决实际问题,训练初步工程设计的能力。根据机械设计制造及其自动化专业的特点,着重培养以下几方面能力: 1调查研究、中外文献检索、阅读与翻译的能力; 2综合运用基础理论、专业理论和知识分析解决实际问题的能力; 3查阅和使用专业设计手册的能力; 4设计、计算与绘图的能力,包括使用计算机进行绘图的能力; 5撰写设计说明书(论文)的能力。 2本毕业设计(论文)课题任务的内容和要求(包括原始数据、技术要求、工作要求等): 一、课题任务内容:设计一种直线型Delta并联机器人,动平台与静平台之间通过三条支链连接。通过安装在固定框架上的三个直流电机结合滚珠丝杠副产生的直线运动,使动平台具有一个平动自由度和两个转动自由度。每个电机安装有编码器用于检测其转角,通过机构运动学建模可计算出动平台的位姿信息,并用于实现对机器人的控制。二、设计要求: 1.外形尺寸600x600x800; 2.竖直方向平移范围:100mm,水平方向转动范围:15; 3.动平台最大承载5kg; 毕 业 设 计(论 文)任 务 书3对本毕业设计(论文)课题成果的要求包括图表、实物等硬件要求: 1.外文专业文献翻译(原文和译文,译文3000汉字以上); 2.毕业设计开题报告一份; 3.编写设计说明书一份; 4.完整的设计图纸一套,运动仿真结果数据以及动画一套。 4主要参考文献: 1蔡自兴机器人学基础 M北京:机械工业出版社,2009. 2丛爽,尚伟伟并联机器人:建模,控制优化与应用 M北京:电子工业出版社, 2010. 3张利敏,梅江平,赵学满,等一种二平动自由度并联机械手动力尺度综合 J天津大学学报, 2010, 43(8):661-666. 4Bouri M, Clavel R. The linear Delta: Developments and applicationsC/The 41st International Symposium on Robotics.Frankfurt, Germany: VDE, 2010: 1198-1205. 5Milutinovic D, Slavkovic N, Kokotovic B, et al. Kinematic modeling of reconfigurable parallel robots based on Delta conceptJ. Journal of Production Engineering, 2012, 15(2): 71-74. 6Rey L, Clavel R. The Delta parallel robotM/Parallel Kinematic Machines. London, UK: Springer, 1999: 401-417. 7Pierrot F, Dauchez P, Fournier A. Fast parallel robotsJ. Journal of Robotic Systems, 1991, 8(6): 829-840. 8徐龙祥,欧阳祖行.机械设计M. 第二版,北京:航空工业出版社,1999. 9李柱.互换性与技术测量M.北京:高等教育出版社,2004. 10哈尔滨工业大学理论力学教研室.理论力学M.北京:高等教育出版社,2009 11王全景,张庆余.48小时精通CREO PARAMETRIC 3.0中文版零组件设计技巧M.北京:电子工业出版,2013. 12范钦珊.材料力学M.北京:清华大学出版社,2008. 13Kosinska A, Galicki M, Kedzior K. Designing and optimization of parameters of Delta-4 parallel manipulator for a given workspaceJ. Journal of Robotic Systems, 2003, 20(9): 539-548. 14杨斌久,蔡光起,罗继曼,等少自由度并联机器人的研究现状 J机床与液压, 2006, 34(5): 202-205. 15黄真,孔令富,方跃法并联机器人机构学理论及控制M北京:机械工业出版社, 1997. 16付萌. 少自由度并联机构尺度参数的多目标优化研究D. 电子科技大学,2013. 毕 业 设 计(论 文)任 务 书5本毕业设计(论文)课题工作进度计划:15.11.20-15.12.20 学生明确选题 15.12.20-16.01.15 学生完成开题报告 16.01.15-16.03.18 学生完成设计草图阶段,明确设计方案 16.03.18-16.04.08 学生完善设计正稿, 撰写毕业设计论文初稿 16.04.08-16.04.30 学生毕业设计完成阶段,提交毕业论文正稿,完成期中检查 16.05.01-16.05.10 学生提交毕业设计论文,布置毕业设计展 16.05.10-16.05.15 布展、毕业答辩准备 所在专业审查意见:同意负责人: 2016 年 1 月18 日 毕 业 设 计(论 文)开 题 报 告设计(论文)题目:三自由度Delta并联机器人的设计与仿真 学生姓名:专业:所在学院:指导教师:职称:年 月日 开题报告填写要求1开题报告(含“文献综述”)作为毕业设计(论文)答辩委员会对学生答辩资格审查的依据材料之一。此报告应在指导教师指导下,由学生在毕业设计(论文)工作前期内完成,经指导教师签署意见及所在专业审查后生效;2开题报告内容必须用黑墨水笔工整书写或按教务处统一设计的电子文档标准格式打印,禁止打印在其它纸上后剪贴,完成后应及时交给指导教师签署意见;3“文献综述”应按论文的框架成文,并直接书写(或打印)在本开题报告第一栏目内,学生写文献综述的参考文献应不少于15篇(不包括辞典、手册);4有关年月日等日期的填写,应当按照国标GB/T 740894数据元和交换格式、信息交换、日期和时间表示法规定的要求,一律用阿拉伯数字书写。如“2004年4月26日”或“2004-04-26”。5、开题报告(文献综述)字体请按宋体、小四号书写,行间距1.5倍。毕 业 设 计(论文) 开 题 报 告 1结合毕业设计(论文)课题情况,根据所查阅的文献资料,每人撰写不少于1000字左右的文献综述: 自从1961年美国Unimation公司推出第一台工业机器人以来,机器人得到了十分迅速的发展。如今机器人已经广泛应用于工业生产中,如喷气、焊接。搬运。装配等工作,在汽车工业、电子工业、核工业、服务业和医疗卫生等许多方面都有应用。现在所说的机器人多指串联机器人。1965年,英国高级工程师Stewart首先提出了一种6自由度的并联机构作为飞行模拟器用于训练飞行员,到1978年,澳大利亚的Hunt教授指出这种机构更接近于人体的结构,可以将此平台作为机器人机构。80年代中期,国际上研究并联机器人的学者还寥寥无几,出的成果也不多,到80年代末期特别是90年代以来,并联机器人才被广为关注,并成为新的热点,许多大型会议都设有专题进行讨论。1985年,Clavel提出了一种成为Delta的三维移动机构。Delta机器人是最经典的空间三自由度移动的并联机构,大多数空间三自由度并联机构都是从Delta机构衍生的。Delta机器人是一种具有3个平动自由度的告诉并联机器人,也是目前商业应用最成功的并联机器人之一。目前,国内外对于并联机器人的研究主要集中于机构学、运动学、动力学和控制策略等几个领域。其中机构学和运动学分析主要研究并联机器人的运动学。奇异形位。工作空间和灵巧度分析等方面,这些研究是实现并联机器人控制和应用的基础。动力学和控制策略的研究主要是对并联机器人进行动力学分析和建模,研究各种可能的控制算法,对并联机器人实时控制,以达到预期的控制效果。随着微电子和计算机技术的发展,并联机器人得到了越来越广泛的应用。工业上,并联机器人可以用在汽车总装线上安装轮胎,汽车发动机,还可以用作飞船对接器,潜艇救援中的对接器,飞行模拟器、空间飞行器对接机构及其地面试验设备,天文望远镜跟踪元位系统等,其中Delta机器人被广泛应用于食品与药品的包装与机械自动生产线上。对于困难的地下工程,也可以利用并联机构。并联机器人的一个重要应用就是被称为“21世纪的机床”的虚拟轴机床。并联机床的中心结构简单,传动链极短,刚度大,质量轻,切削效率高,成本低,很容易实现6轴联动,因而可以加工非常复杂的三维曲面。1994年美国芝加哥IMTS博览会上GIDDING&LEWIS公司推出了新开发的并联式VARJAX“虚拟轴机床”,硬气广泛关注。并联机器人的另一个重要的应用方面是作为微动机构或微型机构。这种机构充分发挥了并联机构空间不大、精度和分辨率高的特点,在三维空间内微小移动在2-20微米之间、如在眼科手术、微细外科手术中的细胞操作、心脏冠状动脉移植等中都得到了很好的应用。l参考文献1蔡自兴机器人学基础 M北京:机械工业出版社,2009. 2丛爽,尚伟伟并联机器人:建模,控制优化与应用 M北京:电子工业出版社, 2010.3张利敏,梅江平,赵学满,等一种二平动自由度并联机械手动力尺度综合 J天津大学学报, 2010, 43(8):661-666. 4Bouri M, Clavel R. The linear Delta: Developments and applicationsC/The 41st International Symposium on Robotics.Frankfurt, Germany: VDE, 2010: 1198-1205. 5Milutinovic D, Slavkovic N, Kokotovic B, et al. Kinematic modeling of reconfigurable parallel robots based on Delta conceptJ. Journal of Production Engineering, 2012, 15(2): 71-74. 6Rey L, Clavel R. The Delta parallel robotM/Parallel Kinematic Machines. London, UK: Springer, 1999: 401-417. 7Pierrot F, Dauchez P, Fournier A. Fast parallel robotsJ. Journal of Robotic Systems, 1991, 8(6): 829-840. 8徐龙祥,欧阳祖行.机械设计M. 第二版,北京:航空工业出版社,1999. 9李柱.互换性与技术测量M.北京:高等教育出版社,2004. 10哈尔滨工业大学理论力学教研室.理论力学M.北京:高等教育出版社,2009 11王全景,张庆余.48小时精通CREO PARAMETRIC 3.0中文版零组件设计技巧M.北京:电子工业出版,2013. 12范钦珊.材料力学M.北京:清华大学出版社,2008. 13Kosinska A, Galicki M, Kedzior K. Designing and optimization of parameters of Delta-4 parallel manipulator for a given workspaceJ. Journal of Robotic Systems, 2003, 20(9): 539-548. 14杨斌久,蔡光起,罗继曼,等少自由度并联机器人的研究现状 J机床与液压, 2006, 34(5): 202-205. 15黄真,孔令富,方跃法并联机器人机构学理论及控制M北京:机械工业出版社, 1997. 16付萌. 少自由度并联机构尺度参数的多目标优化研究D. 电子科技大学,2013.毕 业 设 计(论文) 开 题 报 告 2本课题要研究或解决的问题和拟采用的研究手段(途径): l主要研究内容:1.基座的设计2.末端执行器的设计3.臂杆的设计4.电动机的选型5.传动链的选择6.Delta型并联机器人的布置形式及基本参数的确定 l拟采用的研究手段: 设计一种直线型Delta并联机器人,动平台与静平台之间通过三条支链连接。通过安装在固定框架上的三个直流电机结合滚珠丝杠副产生的直线运动,使动平台具有一个平动自由度和两个转动自由度。每个电机安装有编码器用于检测其转角,通过机构运动学建模可计算出动平台的位姿信息,并用于实现对机器人的控制。在完成设计工作的同时,针对Delta型并联机器人的设计进行分析研究,以便确定其合理的结构和性能参数。毕 业 设 计(论文) 开 题 报 告 指导教师意见:1对“文献综述”的评语:对并联机器人应用于工业领域的研究现状、发展趋势、设计原则、存在问题、未来发展方向作了较丰富的综述,内容充实、条理清晰、表述清楚。 2对本课题的深度、广度及工作量的意见和对设计(论文)结果的预测:本课题涉及一种三自由度Delta并联机器人设计,具有非常现实的应用背景。本设计主要包括三自由度Delta并联机器人结构设计,要求设计者不仅掌握较扎实的机电一体化设计能力,还应掌握较深的机器人专业理论基础,因此本课题较难,工作量较大。本设计的成果应包括三自由度Delta并联机器人结构模型、装配图、零件图、运动仿真等内容。 3.是否同意开题: 同意 不同意 指导教师: 2016 年 03 月 17 日所在专业审查意见:同意 负责人: 2016 年 03 月 17 日毕毕 业业 设设 计(论计(论 文)外文)外 文文 参参 考考 资资 料料 及及 译译 文文译文题目:译文题目:由表面应力引起的纳米多孔金由表面应力引起的纳米多孔金 悬臂梁的宏观弯曲悬臂梁的宏观弯曲学生姓名:学生姓名: 专专业:业: 所在学院:所在学院: 指导教师:指导教师: 职职称:称: Surface-Stress Induced MacroscopicBending of Nanoporous GoldCantileversDominik Kramer,*, Raghavan Nadar Viswanath, and Jo1rg Weissmu1ller,Institut fu r Nanotechnologie, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 76021 Karlsruhe, Germany, and Fachrichtung Technische Physik, UniVersita t des Saarlandes, 66041 Saarbru cken, GermanyReceived January 13, 2004ABSTRACTNANOLETTERS2004 Vol. 4, No. 5793-796We report the preparation of composite foils consisting of two layers, one solid gold and one nanoporous gold. Tip displacements of several millimeters are observed when the foils are immersed in aqueous electrolytes and the electrochemical potential varied. This suggests that nanoporous metals could be used as the active component in actors, and it demonstrates for the first time that changes in the surface stress f of the metalelectrolyte interface can induce a macroscopic strain, orders of magnitude larger than the amplitudes which are reached in conventional cantilever bending experiments used to measure f.Changes of the shape of liquid mercury electrodes in response to changes of the electrical potential have been observed as early as the 19th century. In 1872, Gabriel Lippmann invented his capillary electrometer in which small voltage differences can be measured by observation of the displacement of a mercury meniscus. The Lippmann equation relates the surface tension of a liquid electrode to the electrode potential, and it isalso a good approximation for solids.1 However, the surface stress f of a solid is not even approximately equal to its surface tension , and it exhibits a different (generally, stronger)2dependence on the potential.1 Furthermore, due to the stiffness of solids, potential-dependent changes in the position or shape of solid surfaces are much smaller than those of liquidelectrodes. Highly sensitive extensometers3 were used to monitor the strain, and in the past decade, surface stress changes have been measured using atomic force microscope type techniques: thin metal films on the cantilevers are used as electrodes, and techniques as, for instance, laser beam deflection allow the tip displacement (in the lower nanometer range, e.g., in ref 4) induced by changes in the surface stress tobe measured.5-10 Because the surface stress in solids could hitherto only be detected in a laboratory environment using sophisticated equipment, it might be considered as an “exotic” phenomenon of little practical relevance. Even in thin film growth, where the* Corresponding author. E-mail: Dominik.Kramerint.fzk.de. Ad-dress: Dr. Dominik Kramer, Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, Institut fu r Nanotechnologie, PO Box 3640, D-76021 Karlsruhe, Germany, Tel. +49-(0)7247 82 6379, Fax +49-(0)7247 82 6369. Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe. Universitat des Saarlandes.10.1021/nl049927d CCC: $27.50 2004 American Chemical Societyinterface-induced stress maybe large,its importanceremains the subject to current research.11More recently, surface stress induced length changes of 1.5 m have been observed in nanoporous mm-sized platinum cubes, an indication that the capillary effects can be enhancedby increasing the surface-to-volume ratio ,12 which takes on exceptionally large values in porous nano-structures. Since the pressure in the bulk required to balance the surface stress scales with independent of the geometry of themicrostructure,13 large volume changes and a considerable mechanical work density result from changes in the surface stress of the nanoporous metal.12 Therefore, it has been suggested that such materials may be attractive for use as actuators.14 However, integration of the porous metal into a device requires that it can be precisely and reproducibly shaped, and that it can be bonded to the parts of the device that transmit displacement and load. It has not been demonstrated so far how this can be achieved using nano-powder compacts; furthermore, while powder compacts support a considerable hydrostatic pressure, their resistance to shear stress may be poor. Here, we show that nanoporous metals prepared by dealloying a bulk solid solution exhibit similarly large strain amplitudes as nanopowder compacts, and that the porous material can be joined to solid metal foils to form a composite cantilever beam actuator. The charge-induced expansion or contraction of the porous metal gives rise to a biaxial stress component that results in a large bending of the foil. In this way, the effect of the interface-induced stress is amplified so that the deflection becomes visible to the naked eye: the tip moves by 3 mm, an increasePublished on Web 03/31/2004Figure 1. Scanning electron micrograph of the nanoporous gold structure obtained by etching silver-gold alloy in perchloric acid.by the factor 106 compared to previous cantilever bending experiments using a planar surface. This demonstrates that changes in the surface stress of nanoporous metals can be exploited to do work in cantilever bending, analogously towhat was recently reported for carbon nanotubes,15 vanadium oxide nanofibers,16 and conducting polymers.17Dealloying, the selective dissolution of the less noble component from a solid solution, is well-known to result innanoporous structures.18 Dealloying is attractive as a tech-nique for preparing nanoporous solids since it can be applied irrespective of the shape of the active part of a device - including, conceivably, lithographically shaped miniaturizedcomponents. Our samples were obtained by the dealloyingof Ag75Au25 master alloy sheets (see Methods). Figure 1 shows a scanning electron microscopy image of the nano-porous gold microstructure. The ligament size is ca. 20 nm.Cuboids of porous gold of dimension 1.21.2 1 mm3 were investigated in a commercial dilatometer equipped with an in-situ electrochemical cell. Figure 2A is the cyclic voltammogram (current vs potential curve) of a nanoporous gold sample immersed in 50 mM sulfuric acid, recorded in-situ in the dilatometer cell. The potential limits are given by the onset of hydrogen evolution (ca. -0.25 V) and gold oxidation (above 1 V). The voltammogram in Figure 2A is typical of a polycrystalline gold surface: The current is almost constant over the entire potential range, indicating a continuous capacitive double-layer charging anddischarging, in agreement with the known tendency of SO4-anions to interact only weakly with Au.19Figure 2B shows the change L in sample length versus the time as the potential is cycled between -0.26 and +1.05 V in 50 mM H2SO4. The length changes periodically and reversibly with the potential, with a small irreversible shrinking superimposed to that. When the reversible part of L is plotted versus the potential (Figure 2C), it is apparent that the length of the sample can be changed reproducibly by controlling the potential, with a small hysteresis of 0.1 V (or 0.02 m). The charge was obtained by integration of the current of Figure 2A and by setting the potential of zero charge (pzc) to 0.25 V compare ref 20. The graph of strain versus charge (Figure 2E) is highly reversible and linear bothFigure 2. In-situ dilatometry using 15 succesive cycles of the potential of a cuboid nanoporous gold sample in 50 mM sulfuric acid. (A)Cyclic voltammogram (current I versus the electrochemical potential E). (B) Length change L versus time t during the 15 cycles of (A).(C) Reversible part of L versus E, obtained by subtraction of an constant arbitrary value for each cycle. (D) Total charge Q versus E.(E) L/L0 versus Q. (A) and (C)-(E) display results of all 15 cycles superimposed.794Nano Lett., Vol. 4, No. 5, 2004in the negatively and positively charged regimes; it exhibits a change in slope near the pzc. A similar linear correlation has been observed for a Au(111) surface by STM,21,22 but the break near the pzc of Figure 2E was not resolved there.It is a matter of debate in how far the potential dependence of the surface stress reflects the details of the bonding of adsorbates to the surface (see ref 10 and references therein). We have carried out experiments using perchloric acid as the electrolyte, and found the results to be in qualitative agreement with Figure 2 (see Supporting Information). Sincethe ClO4- ion adsorbs even more weakly than SO4-, this finding is compatible with the notion that the potential-induced strain does not intrinsically require the formation of the chemical bonds involved in specific adsorption; this would imply that the change in surface stress reflects the modifiedbonding in the space-charge layer within the metal surface.2,12 Two further observations in support of this notion are: (i) whereas we find Au to contract at negative potential, carbon nanotubes show the opposite effect, expansion upon negativecharging,15 which indicates that the change in surface stress is strongly related to the nature of the bonding in the solid; and (ii) in-situ X-ray adsorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) data show a significant change in d-band occupancy in Pt nanoparticles as the Pt-electrolyte interface is charged, confirming that the superficial electronic structure of the solidcan be changed.23 If the change in surface stress and the surface-induced strain in our samples are indeed a consequence of the modified bonding in the metal, then theresults provide support for a more general concept:24 by controlling the net charge in space-charge layers at metal surfaces, one can modify the electronic density of states and, thereby, the local properties of the matter at the surface. In nanomaterials, which have a large surface-to-volume ratio, this will result in changes of the overall properties, opening a way for tuning all those materials properties that depend on the density of states.The action of the surface stress can be amplified by use of bilayer foils. Each of the foils consists of a layer of porous Au bonded to a layer of solid Au, see the cross-sections in Figure 3A. When the foil is immersed in an electrolyte, and its potential varied, then the porous layer will tend to expand or contract, whereas the solid layer will tend to maintain its dimensions. This will result in shear stress at the interface between the two layers, and in a bending of the foil, quite analogous to the effect of the differential thermal expansion used in bimetal thermometers. A similar arrangement has alsobeen used to produce carbon nanotube actuators.15To make the bilayer foils, a 2 mm thick sheet of silver-gold alloy was cold-welded to a 0.5 mm thick sheet of pure gold by rolling. After reducing the thickness of the stack to 30 m by further rolling, the resulting foil was annealed for stress relief and strips 35-40 mm long and 2 mm wide cut from it. Dealloying resulted in a composite foil consisting of a 6 m thick layer of solid Au covered with 24 m of porous Au. Twofoils were immersed in 1 M HClO4 and wired as the working and the counter electrodes, respectively. Figures 3A and 3B show a schematic drawing and a photograph of the experimental setup. Both foils undergo aNano Lett., Vol. 4, No. 5, 2004Figure 3. Illustration of the operation of the composite foils. (A) schematic cross-section through an electrochemical cell comprising two identical foils that serve (interchangeably) as working electrode and counter electrode. (B-D) photographs of an electrochemical cell with two bimetallic stripes (nanoporous gold on gold), similar to the schematic in (A). The electrolyte is 1 M perchloric acid. The lower scale of the ruler is calibrated in mm. (C, D) Two enlarged views of the cell in (B), showing the tip of one of the foils with two different voltages applied between the two foils, +1 V (C) and -1 V (D). It is seen, that when the voltage is inversed, the tip moves by ca. 3 mm. The arrows serve as reference markers, emphasizing the tip displacement.reversible bending as the voltage is changed. Figures 3C,D show enlarged views of the tip of one of the foils before and after inverting the applied voltage. When the potential difference between the electrodes is switched from -1 V to +1 V, the tip moves by as much as 3 mm. Thus, compared to cantilever bending experiments using planar surfaces, the displacement resulting from surface stress changes has increased from few nanometers to the millimeter regime,that is, by about a factor of 106. A video clip showing the actuator operation is displayed as Supporting Information. For the first time, the effects potential-induced changes of the interface stress, which had previously required sophisticated experimental equipment, have become visible to the naked eye.For actuator applications, the response time is important. Figure 4A shows the time-dependent L during a series of795Figure 4. (A) Length change L of the sample in 50 mM sulfuric acid versus time, measured in the dilatometer during a series of potential jumps from -0.2 to 1 V and back (dashed line: potential).(B) Frequency dependence of the amplitude during potential jumps (rectangular wave) in sulfuric acid. Large squares: Amplitude of the charge curve. Small circles: Amplitude of the length change as measured in the dilatometer. The dilatometersmaximum sampling rate of 10 s-1 limits the experimental strain amplitude at high frequency.potential jumps from -0.2 V to 1 V and back. The half-times of the jumps in current and strain are 220 and 270 ms.Because of the limited sampling rate (10 s-1) of the dilatometer, the time constant obtained from the charging curves is considered more accurate. The strain amplitude at a frequency of 0.3 Hz is almost identical to that during slower switching (Figure 4B), which is consistent with the response time given above. The bilayer foils react similarly fast, despite the drag of the electrolyte. The intrinsic time scale is given by the time constant of the charging current, which was determined as 25 ms, considerably faster than in the thicker dilatometer samples. This agrees qualitatively with the expectation that the drift of ions into the pores will be accelerated as the path is shortened.The large mechanical response induced by changes in the surface stress predestines porous gold as an active component in sensors, especially if its surface is modified by adsorption, e.g., of molecules functionalized by thiol groups. These can be chosen to react selectively with specific molecules, for instance, antibodies; the reaction changes the surface stress, e.g., by steric repulsion of the product, and sensors detectingthese changes have been proposed and tested.8,25-27 Their sensitivity may be significantly enhanced by using nano-porous layers instead of planar surfaces.In addition to its performance as a simple actor producing reversible strain controlled by an applied voltage, the deviceshown in Figure 3 can also be regarded as a primitive voltmeter. If the tip displacement was observed with an optical microscope as in Lippmanns device, it would be suited to measure small voltage differences. Thus, Lipp-manns 19th century voltmeter based on changes of the surface tension of liquid mercury interface has found a modern equivalent based on changes in the surface stress of a solid metal.Acknowledgment. Stimulating discussions with H. Gle-iter and support by DFG (Center for Functional Nanostruc-tures) are gratefully acknowledged.Supporting Information Available: Experimental de-tails, two additional Figures (S1, S2), and a video showing the movement of the bilayer foils. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at .References(1) Lipkowski, J.; Schmickler, W.; Kolb, D. M.; Parsons, R. J. Elec-troanal. Chem. 1998, 452, 193-197.(2) Schmickler, W.; Leiva, E. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 453, 61-67.(3) Lin, K. F.; Beck, T. R. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1976, 123, 1145-1151.(4) Haiss, W.; Sass, J. K. J. Electronanl. Chem. 1995, 386, 267-270.(5) Ibach, H. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1997, 29, 195-263. Ibach, H. Surf. Sci. Rep.1999, 35, 71-73.(6) Raiteri, R.; Butt, H.-J. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 15728-15732.(7) Miyatani, T.; Fujihira, M. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 7099-7115.(8) Ibach, H.; Bach, C. E.; Giesen, M.; Grossmann, A. Surf. Sci. 1997, 375, 107-119.(9) Raiteri, R.; Butt, H.-J.; Grattarola, M. Electrochim. Acta 2000, 46, 157-163.(10) Friesen, C.; Dimitrov, N.; Cammarata, R. C.; Sieradzki, K.Langmuir 2001, 17, 807-815.(11) Cammarata, R. C.; Trimble, T. M.; Srolovitz, D. J. J. Mater. Res. 2000, 15, 2468-2474.(12) Weissmu ller, J.; Viswanath, R. N.; Kramer, D.; Zimmer, P.; Wu rschum, R.; Gleiter, H. Science 2003, 300, 312-315.(13) Weissmu ller, J.; Cahn, J. W. Acta Mater. 1997, 45, 1899-1906.(14) Baughman, R. H. Science 2003, 300, 268-269.(15) Baughman, R. H.; Cui, C.; Zakhidov, A. A.; Iqbal, Z.; Barisci, J. N.; Spinks, G. M.; Wallace, G. G.; Mazzoldi, A.; De Rossi, D.; Rinzler, A. G.; Jaschinski, O.; Roth, S.; Kertesz, M. Science 1999, 284, 1340-1344.(16) Gu, G.; Schmid, M.; Chiu, P.-W.; Minett, A.; Fraysse, J.; Kim, G.-T.; Roth, S.; Kozlov, M.; Mun oz, E.; Baughman, R. H. Nature Mater. 2003, 2, 316-319.(17) Baughman, R. H. Synth. Met. 1996, 78, 339-353.(18) Erlebacher, J.; Aziz, M. J.; Karma, A.; Dimitrov, N.; Sieradzki, K.Nature 2001, 410, 450-453.(19) Kolb, D. M. Prog. Surf. Sci. 1996, 51, 109-173.(20) Kramer, D., Thesis, University of Ulm, Germany, 2000.(21) Haiss, W.; Nichols, R. J.; Sass, J. K.; Charle, K. P J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998, 452, 199-202.(22) Nichols, R. J.; Nouar, T.; Lucas, C. A.; Haiss, W.; Hofer, W. A.Surf. Sci. 2002, 513, 263-271.(23) Mukerjee, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Soriaga, M. P.; McBreen, J. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1995, 142, 1409-1422.(24) Gleiter, H.; Weissmu ller, J.; Wollersheim, O.; Wu rschum, R.Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 737-745.(25) Berger, R.; Delamarche, E.; Lang, H. P.; Gerber, Ch.; Gimzewski, J. K.; Meyer, E.; Gu ntherodt, H.-J. Science 1997, 276, 2021-2024.(26) Chen, G. Y.; Thundat, T.; Wachter, E. A.; Warmack, R. J. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 77, 3618-3622.(27) Fritz, J.; Baller, M. K.; Lang, H. P.; Strunz, T.; Meyer, E.; Gu ntherodt, H.-J.; Delamarche, E.; Gerber, Ch.; Gimzewski, J. K. Langmuir 2000, 16, 9694-9696.NL049927D796Nano Lett., Vol. 4, No. 5, 2004本文研究了一种双层复合材料箔的制备,其中一层为固体金,另一层为纳米多孔金。当箔浸入电解质水溶液中,并改变溶液的电化学势,可以观察到数毫米大小的端部位移。这一现象表明纳米多孔金属可以作为作动器中的应激组件,还首次揭露了金属-电解液界面上表面应力 f 的改变将引起宏观应变,该应变的大小比用于测量表面应力f 的传统悬臂梁弯曲实验中所能达到的振幅要高几个数量级。早在 19 世纪,人们就已观察到,在电势改变时液态汞电极将会产生形状改变。1872 年,Gabriel Lippmann(加布里埃尔李普曼,外国人的名字不必翻译)发明了毛细静电计,可通过观察一个水银弯曲面的位移来测得微小的电压改变。李普曼方程建立了液态电极的表面张力和电极电势的相关关系,而且对固体电极也可以获得令人满意的近似结果 1。然而,固体的表面应力 f 并不近似等于其表面张力 ,并表现出对电势的不同依赖性 1(一般而言依赖性更强)2。进一步讲,由于固体具有一定的刚度,其表面依赖于电势的位置和形状改变远小于液体电极。高敏延展计 3 用于监测应变,在过去的十年间,利用原子力显微镜技术已可测量表面应力的改变:将薄金属片置于悬臂梁上作为电极,然后采取激光束偏转分析技术,就可以得到由表面应力改变引起的悬臂梁末端位移(可达到纳米级,如参 4)5-10。然而由于目前仅能在实验室环境内依托精密仪器检测到固体的表面应力,所以这一发现还只被视作一种缺少实用价值的“独特”现象。即使在界面导致应力较大的薄膜生长方面,其重要性也有待进一步研究 11。最近,在具有毫米量级尺寸的纳米多孔铂立方体上观测到了由于表面应力引起的长度变化,达到 1.5m。这说明提高表体比 能够放大毛细管效应 12,而多孔纳米结构的表体比非常大。由于块体材料中平衡表面应力所需的体积应力会随 变化,而 不依赖于微观结构的几何特性,所以纳米多孔金属的表面应力变化将引起可观的机械功密度及大的体积改变 12。因此,这类金属被认为在作动器制造方面前景诱人 14。然而,将多孔金属集成在设备上

- 温馨提示:

1: 本站所有资源如无特殊说明,都需要本地电脑安装OFFICE2007和PDF阅读器。图纸软件为CAD,CAXA,PROE,UG,SolidWorks等.压缩文件请下载最新的WinRAR软件解压。

2: 本站的文档不包含任何第三方提供的附件图纸等,如果需要附件,请联系上传者。文件的所有权益归上传用户所有。

3.本站RAR压缩包中若带图纸,网页内容里面会有图纸预览,若没有图纸预览就没有图纸。

4. 未经权益所有人同意不得将文件中的内容挪作商业或盈利用途。

5. 人人文库网仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对用户上传分享的文档内容本身不做任何修改或编辑,并不能对任何下载内容负责。

6. 下载文件中如有侵权或不适当内容,请与我们联系,我们立即纠正。

7. 本站不保证下载资源的准确性、安全性和完整性, 同时也不承担用户因使用这些下载资源对自己和他人造成任何形式的伤害或损失。

人人文库网所有资源均是用户自行上传分享,仅供网友学习交流,未经上传用户书面授权,请勿作他用。

川公网安备: 51019002004831号

川公网安备: 51019002004831号